![[Home]](http://www.bayleshanks.com/cartoonbayle.png)

Table of Contents for Programming Languages: a survey

This is not a book about how to implement a programming language. However, even at the earliest stages of language design, it is valuable to have some idea of how the certain choices in the design of the language could make the implementation much less efficient or much more difficult to write. For this purpose, we'll provide a cursory overview of implementation topics, touching as we go on some of the language design choices that may have a large impact.

when do we convert to normal forms?

todo

" The first big phase of the compilation pipeline is parsing. You need to take your input and turn it into a tree. So you go through preprocessing, lexical analysis (aka tokenization), and then syntax analysis and IR generation. Lexical analysis is usually done with regexps. Syntax analysis is usually done with grammars. You can use recursive descent (most common), or a parser generator (common for smaller languages), or with fancier algorithms that are correspondingly slower to execute. But the output of this pipeline stage is usually a parse tree of some sort.

The next big phase is Type Checking. ...

The third camp, who tends to be the most isolated, is the code generation camp. Code generation is pretty straightforward, assuming you know enough recursion to realize your grandparents weren't Adam and Eve. So I'm really talking about Optimization...

-- http://steve-yegge.blogspot.ca/2007/06/rich-programmer-food.html

modified from Python's docs:

" The usual steps for compilation are:

Parse source code into a parse tree

Transform parse tree into an Abstract Syntax Tree

Transform AST into a Control Flow Graph

Emit bytecode based on the Control Flow Graph" -- https://docs.python.org/devguide/compiler.html#abstractdiscussions on the benefits of the introduction of a 'Core' or 'middle' language in between the HLL AST and a lower-level, LLVM-ish language:

some advantages of a core language:

Links:

todo: somewhere put my observations on LLLs and target languages:

'target' languages include both 'Core languages' and LLLs

goal for:

Core languages tend to be: similar to the HLL, except: de-sugared (eg apply various local 'desugar' tranformations) have fewer primitives than the HLL (eg de-sugaring various control flow constructs to GOTO) in safe or prescriptive languages, sometimes the Core primitives are more powerful than the HLL (eg in Rust the MIR core language has GOTO but Rust does not) still retain function calling have explicit types have a bunch of other things that are explicit, so that the LLL is way to verbose for human use, but with a similar control flow to the original HLL like the HLL but unlike LLL, still nonlinear (parethesized subexpressions are still present)

LLLs and 'assembly' languages are more similar to each other than you might expect.

LLL general properties:

Main families of LLLs: imperative * stack vs. register machines stack machines (eg JVM, Python's, mb Forth) register machines * 3-operand vs 2- or 1-operand register machines * various calling conventions * addressing modes LOAD/STORE vs addressing modes vs LOAD/STORE with constant argument but self-modifying code explicit constant instructions (eg ADDC) vs constant addressing mode vs LOADK * are registers and memory locations actual memory locations upon which address arithmetic can be done (like in assembly), or just variable identifiers (like in Lua)? functional * eg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SECD_machine combinator * eg Nock

Also, instruction encodings might be fixed-width or variable (most are variable).

Primitive operations in LLLs: not as much variance as you might expect. Generally:

Links regarding stack machine vs register machines:

---

Someone's response to the question "Does anyone know if there is research into the effects of register counts on VMs?":

" Someone 1819 days ago [-]

If you can map all VM registers to CPU registers, the interpreter will be way simpler.

If you have more VM registers than CPU registers, you have to write code to load and store your VM registers.

If you have more CPU registers than VM registers, you will have to write code to undo some of the register spilling done by the compiler (if you want your VM to use the hardware to the fullest.)

So, the optimum (from a viewpoint of 'makes implementation easier') depends on the target architecture.

Of course, a generic VM cannot know how many registers (and what kinds; uniform register files are not universally present) the target CPU will have.

That is a reason that choosing either zero (i.e. a stack machine) or infinitely many (i.e. SSA) are popular choices fo VMs: for the first, you know for sure your target will not have fewer registers than your VM, for the second, that it will not have more.

If you choose any other number of VM registers, a fast generic VM will have to handle both cases.

Alternatively, of course, one can target a specific architecture, and have the VM be fairly close to the target; Google's NaCl? is (was? I think they changed things a bit) an extreme example. I have not checked the code, but this, I think, is similar. " -- https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=2930109

---

whole program analysis

if modules are separately compiled and allow types to remain completely abstract, e.g. when a module is compiled it is possible to not know what the in-memory representation of values in the module will be, then a host of optimizations cannot be performed. Alternatives:

see section "compilation model" in "Retrospective Thoughts on BitC?" http://www.coyotos.org/pipermail/bitc-dev/2012-March/003300.html

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=5422094

" Some common intermediate representations:

Examples:

-- [5]

[6] also describes and motivates SSA and CPS in more detail. It defines SSA and explains why you need phi in SSA, and refers to an algorithm to determine where to place the phis.

Abstract machines and the compilers that love/hate them

Some target languages, such as WASM and SPIR V, require some amount of structure in control flow. If the source language doesn't provide this structure, it must be introduced.

Links:

check to see if there are any reads to uninitialized variables could implement as types

issue in C:

in C, according to one of the comments on http://www.slideshare.net/olvemaudal/deep-c , it was claimed (i didn't check) that if you declare your own printf with the wrong signature, it will still be linked to the printf in the std library, but will crash at runtime, e.g. "void printf( int x, int y); main() {int a=42, b=99; printf( a, b);}" will apparently crash.

-- A new programming language might want to throw a compile-time error in such a case (as C++ apparently does, according to the slides).

Links:

atomics

SIMD, MIMD

GPU

"Instructions should not bind together operations which an optimizing compiler might otherwise choose to separate in order to produce a more efficient program."

tags

descriptors

stacks

cactus/saguaro stacks

random book on stack-based hardware architectures: http://www.ece.cmu.edu/~koopman/stack_computers/contents.html

trampolines

vtables (C++)

interpreter vs spec:

" The technique that we had for Smalltalk was to write the VM in itself, so there’s a Smalltalk simulator of the VM that was essentially the only specification of the VM. You could debug and you could answer any question about what the VM would do by submitting stuff to it, and you made every change that you were going to make to the VM by changing the simulator. After you had gotten everything debugged the way you wanted, you pushed the button and it would generate, without human hands touching it, a mathematically correct version of C that would go on whatever platform you were trying to get onto." -- Alan Kay, http://queue.acm.org/detail.cfm?id=1039523

metacircular interpreters

Futamura projections https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=7061913

"

nostrademons 1 day ago

| link |

IIUC PyPy? is all 3 Futamura projections.

I'm a little rusty on the details, but IIUC the core of PyPy? is an "abstract interpreter" for a restricted subset of Python known as RPython. Abstract interpretation is essentially a fold (in the functional programming sense) of the IR for a language, where you can parameterize the particular operation applied to each node. When the operation specified is "evaluate", you get partial evaluation, as described in the Wikipedia article.

The interesting part of PyPy? happens when the RPython program to be evaluated is itself a Python interpreter, which it is. In this case, 'prog' is the Python interpreter written in RPython, and Istatic is your Python program. The first Futamura projection will give you a JIT; you specialize the RPython interpreter with your particular program, and it evaluates everything statically known at compile time (namely, your program) and produces an executable.

The second Futamura projection will give you a JIT compiler. Remember, since RPython is a subset of Python, an interpreter for Python written in RPython could be interpreted by itself. Moreover, it could be compiled by itself by the process described in the paragraph above. When you compile your JIT through the same process, you get a program that means the same thing (i.e. it will translate a Python program into an executable) but runs faster. The PyPy? JIT that everybody's excited about for running Python scripts faster is this executable.

The third Futamura projection involves running PyPy? on the toolchain that generated PyPy?. Remember, this whole specializer machinery is all written in RPython, which can be interpreted by itself. So when your run the specializer machinery through itself, you get - an optimized toolset for building JIT compilers. That's what made programming language theorists excited about PyPy? long before the Python community was. It's not just "faster Python", but it's a toolset for building a JIT out of anything you can build an interpreter for. Write an interpreter in RPython - for anything, Ruby, PHP, Arc, whatever - and run it through the PyPy? toolchain, and it will give you a JIT compiler.

reply "

https://www.semipublic.comp-arch.net/wiki/ROMmability

http://www.quora.com/What-is-the-difference-between-PyPy-Parrot-and-LLVM

http://lambda-the-ultimate.org/node/2634

Links:

"Basic block": "a portion of the code within a program with only one entry point and only one exit point." (wikipedia)

"in CPS, as in SSA or ANF, expressions don't have subexpressions." -- http://wingolog.org/archives/2014/05/18/effects-analysis-in-guile

"If an intermediate language is in SSA form, then every variable has a single definition site. Single-assignment is a static property because in a general control flow graph the assignment might be in a loop. SSA form was developed by Wegman, Zadeck, Alpern, and Rosen [4, 37] for efficient computation of data flow problems, such as global value numbering and detecting equality of variables." -- https://synrc.com/publications/cat/Functional%20Languages/AliceML/christian_mueller_diplom.pdf , Chapter 3

For example (examples taken from https://synrc.com/publications/cat/Functional%20Languages/AliceML/christian_mueller_diplom.pdf ), if the source code is: x = a + b; y = x + 1; x = a + 1;

then this is equivalent to:

x1 = a + b; y1 = x1 + 1; x2 = a + 1;

When two control flow edges join, we have to do something else. Consider

if x < 5 then v = 1 else v = 2; w = v + 1;

In this v, v has two possible definition sites, violating SSA, but we don't know statically which one will be used. As a control flow graph, we have a diamond:

(if x < 5) / \ / \(v1 = 1) (v2 = 2) \ / \ / (w = v? + 1)

SSA deals with this by introducing a "magic" operator, Phi. Phi is only allowed to occur at the beginning of a basic block. Its semantics are that Phi "knows" when it executes from which basic block control was recently passed to it; it is given multiple arguments, and it simple returns one of them; it chooses which one of its various arguments to return based on from which basic block control was recently passed to it. For example, the above diamond can be replaced by:

(if x < 5) / \ / \(v1 = 1) (v2 = 2) \ / \ / (v3 = Phi(v1,v2)

(w = v3 + 1)

here, Phi will return v1 if control came to it by the left path, or it will return v2 if control came to it by the right path. Meaning that v3 will end up being equal to v1 if the left path is taken, and it will end up being equal to v2 if the right path is taken. Note that the SSA property is preserved; each variable is assigned to exactly once.

"SSA form is typically used as intermediate representation for imperative languages. The functional programming community prefers the λ-calculus and continuations as intermediate language. Andrew Appel pointed out the close relationship between the two representations in his article ”SSA is Functional Programming”" -- https://synrc.com/publications/cat/Functional%20Languages/AliceML/christian_mueller_diplom.pdf

"AliceML? uses a weakening of SSA called Executable SSA Form, which works only on acyclic (control?) graphs, and which does not require Phi nodes. See https://synrc.com/publications/cat/Functional%20Languages/AliceML/christian_mueller_diplom.pdf Chapter 3, section 3.1.1. One disadvantage of that is that "the removal of Phi-functions in the abstract code might artificially extend the liveness of a variable across branches. Suppose a left branch sets a variable at the beginning and the right branch synchronizes this variable at the end. Then, the variable is declared to be live over the whole right branch. This increases register pressure and decreases code quality for register-poor architectures."

A good, simple description of phi nodes: https://capra.cs.cornell.edu/bril/lang/ssa.html

" A program is in SSA form if: 1. each definition has a distinct name 2. each use refers to a single definition ... Main interest: allows to implement several code optimizations " -- http://www.montefiore.ulg.ac.be/~geurts/Cours/compil/2014/05-intermediatecode-2014-2015.pdf

"

Transforming a 3-address representation into stack is easier than a stack one into 3-address.

Your sequence should be the following:

Form basic blocks

Perform an SSA-transform

Build expression trees within the basic blocks

Perform a register schedulling (and phi- removal simultaneously) to allocate local variables for the registers not eliminated by the previous step

Emit a JVM code - registers goes into variables, expression trees are trivially expanded into stack operationsshareeditflag answered Dec 8 '11 at 8:18 SK-logic 8,60612032

Wow! Thanks this is just what I was looking for. Questions: do I need to do the SSA transform within each basic block or across the whole procedure? Do you have any pointers to tutorials, textbooks or other resources? – akbertram Dec 8 '11 at 9:09 SSA transform is aways procedure-wide: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single_static_assignment You'll just need to find a dominance frontier for each basic block where you're assigning a variable (with multiple assignment locations), insert the phi nodes there and then get rid of the redundant phis (n.b.: some may have circular dependencies). – SK-logic Dec 8 '11 at 9:13 @akbertram, LLVM can be a useful source of inspiration here, you can safely model your intermediate representation after it. Some important design decisions from there: do not allow to assign one register to another, and do not allow to assign a constant to a register, always substitute it in place instead. – SK-logic Dec 8 '11 at 9:16 The expression tree looks alot like the original AST -- is it worth making a round-trip through a TAC-like IR or does another sort of IR make sense when the only target is the JVM? – akbertram Dec 8 '11 at 9:17 @akbertram, if you can stuff your JVM compilation before making TAC - then yes, you do not need it, a direct stack code generation is easier. Otherwise, if you can only stack on top of the existing compiler infrastructure, you'll need to re-construct the expression trees. Funny bit is that the JIT will do it again too. – SK-logic Dec 8 '11 at 9:22 " -- [7]

Alternatives to Phi nodes in SSA:

Links:

See e.g.

CPS vs. SSA: http://wingolog.org/archives/2011/07/12/static-single-assignment-for-functional-programmers

"in CPS, as in SSA or ANF, expressions don't have subexpressions." -- http://wingolog.org/archives/2014/05/18/effects-analysis-in-guile

" There are a couple of things going on with CPS as implemented in this style of compilers that make it particularly nice for writing optimization passes:

1) There are only function calls ("throws") and no returns. Though there's no theoretical reduction in the stuff you have to track (since what is a direct-style return is now a throw to the rest of the program starting at the return point), there's a huge reduction in in the complexity of your optimizations because you're not tracking the extra thing. For some examples, you can look in the Manticore codebase where even simple optimizations like contraction and let-floating are implemented in both our early direct-style IR (BOM) and our CPS-style IR (CPS). The latter is gobs more readable, and there's no way at all I'd be willing to port most of the harder optimizations like reflow-informed higher-order inlining or useless variable elimination to BOM.

2) IRs are cheap in languages like lisp and ML. So you write optimizations as a tree-to-tree transformation (micro-optimization passes). This style makes it much easier to enforce invariants. If you look at the internals of most compilers written in C++, you'll see far fewer copies of the IR made and a whole bunch of staged state in the object that's only valid at certain points in the compilation process (e.g., symbols fully resolved only after phase 2b, but possibly invalid for a short time during optimization 3d unless you call function F3d_resolve_symbol...). Just CPS'ing the representation of a C++ compiler without also making it easy to write your optimization passes as efficient tree-to-tree transformations will not buy you much, IMO. " -- [10]

" So the lineage of the CPS-as-compiler-IR thesis goes from Steele's Rabbit compiler through T's Orbit to SML/NJ. At which point Sabry & Felleisen at Rice published a series of very heavy-duty papers dumping on CPS as a representation and proposing an alternate called A-Normal Form. ANF has been the fashionable representation for about ten years now; CPS is out of favor. This thread then sort of jumps tracks over to the CMU ML community, where it picks up the important typed-intermediate-language track and heads to Cornell, and Yale, but I'm not going to follow that now. " -- http://www.paulgraham.com/thist.html

?

"in CPS, as in SSA or ANF, expressions don't have subexpressions." -- http://wingolog.org/archives/2014/05/18/effects-analysis-in-guile

http://lambda-the-ultimate.org/node/1617#comment-19700

http://lambda-the-ultimate.org/node/69

see Optimizing compilers for structured programming languages by Marc Michael Brandis

https://github.com/cfallin/rfcs/blob/cranelift-egraphs/accepted/cranelift-egraph.md

Many large books have been filled with the details of writing efficient compilers and interpreters, so this chapter will only provide an overview of selected techniques.

Calling a function typically involves manipulating the stack (upon entry, you gotta push the return address and the frame pointer register onto the stack, push the formal parameters onto the stack, adjust the top-of-the-stack pointer register, and adjust the frame pointer register to point to the new current stack position).

You can save this overhead by inlining.

Some languages present a computation model in which there is only a stack, no registers. In this case, assuming that the underlying hardware has registers, it may speed things up to use some of the registers to hold the top few stack positions.

Dynamic loading: Languages with dynamic loading can experience slow startup times if they:

See also relevant section of [11].

Links:

Links:

Languages without a canonical implementation tend to:

Scheme started out as an implementation, was described in a series of published papers (the Lambda Papers), turned into a standard, however

Haskell started out as a standard (todo confirm), then many implementations sprung up, then one won out (GHC). As of this writing, GHC has stopped maintaining conformance with the language standard (except while running in a special mode that is not interoperable with most libraries in the wild; see [12] ), and discussions regarding changing the language appear to revolve around changing GHC first, with updates to the standard to cause them to conform to GHC an afterthought [13].

benefits, costs (lots of popular languages dont)

portability

kernel approach

There is always the 'chain solution': Every self-hosting language had to be bootstrapped from another language at the beginning. And each subsequent self-hosting version of a self-hosting language had to be compilable by the previous version. So, to bootstrap the language onto a new platform, one could simply re-boostrap that same early version of the language, and then re-compile each version of the language's compiler in sequence (see eg [14]). Disadvantages to this include: (a) if you are worried about Thompson 'trusting trust' attacks (see section below), then you must audit the source code of each version of the language implementation in this chain; and (b) this seems like a lot more compilation steps than should be necessary.

Another option is for the language to deliberately restrict its own implementation to using code compatible with an earlier version of itself (eg Golang [15]). This removes some of the benefits of a self-hosting language in terms of using the compiler as a way for the language designers to eat their own dogfood.

various stories of standards processes and advice on what to do if you find yourself involved in a standards process:

Ken Thompson wrote a popular essay in which he pointed out that a compiler could be subverted to introduce attacker-desired behavior into the programs it compiles; if the subversion is clever, then such a compiler, when compiling itself from source, would continually re-introduce the subversion.

Links:

" 1.4 WHY ARE STACKS USED IN COMPUTERS?

Both hardware and software stacks have been used to support four major computing areas in computing requirements: expression evaluation, subroutine return address storage, dynamically allocated local variable storage, and subroutine parameter passing.

1.4.1 Expression evaluation stack

Expression evaluation stacks were the first kind of stacks to be widely supported by special hardware. As a compiler interprets an arithmetic expression, it must keep track of intermediate stages and precedence of operations using an evaluation stack. In the case of an interpreted language, two stacks are kept. One stack contains the pending operations that await completion of higher precedence operations. The other stack contains the intermediate inputs that are associated with the pending operations. In a compiled language, the compiler keeps track of the pending operations during its instruction generation, and the hardware uses a single expression evaluation stack to hold intermediate results.

To see why stacks are well suited to expression evaluation, consider how the following arithmetic expression would be computed:

X = (A + B) * (C + D)

First, A and B would be added together. Then, this intermediate results must be saved somewhere. Let us say that it is pushed onto the expression evaluation stack. Next, C and D are added and the result is also pushed onto the expression evaluation stack. Finally, the top two stack elements (A+B and C+D) are multiplied and the result is stored in X. The expression evaluation stack provides automatic management of intermediate results of expressions, and allows as many levels of precedence in the expression as there are available stack elements. Those readers who have used Hewlett Packard calculators, which use Reverse Polish Notation, have direct experience with an expression evaluation stack.

The use of an expression evaluation stack is so basic to the evaluation of expressions that even register-based machine compilers often allocate registers as if they formed an expression evaluation stack.

1.4.2 The return address stack

With the introduction of recursion as a desirable language feature in the late 1950s, a means of storing the return address of a subroutine in dynamically allocated storage was required. The problem was that a common method for storing subroutine return addresses in non-recursive languages like FORTRAN was to allocate a space within the body of the subroutine for saving the return address. This, of course, prevented a subroutine from directly or indirectly calling itself, since the previously saved return address would be lost.

The solution to the recursion problem is to use a stack for storing the subroutine return address. As each subroutine is called the machine saves the return address of the calling program on a stack. This ensures that subroutine returns are processed in the reverse order of subroutine calls, which is the desired operation. Since new elements are allocated on the stack automatically at each subroutine call, recursive routines may call themselves without any problems.

Modern machines usually have some sort of hardware support for a return address stack. In conventional machines, this support is often a stack pointer register and instructions for performing subroutine calls and subroutine returns. This return address stack is usually kept in an otherwise unused portion of program memory.

1.4.3 The local variable stack

Another problem that arises when using recursion, and especially when also allowing reentrancy (the possibility of multiple uses of the same code by different threads of control) is the management of local variables. Once again, in older languages like FORTRAN, management of information for a subroutine was handled simply by allocating storage assigned permanently to the subroutine code. This kind of statically allocated storage is fine for programs which are neither reentrant nor recursive.

However, as soon as it is possible for a subroutine to be used by multiple threads of control simultaneously or to be recursively called, statically defined local variables within the procedure become almost impossible to maintain properly. The values of the variables for one thread of execution can be easily corrupted by another competing thread. The solution that is most frequently used is to allocate the space on a local variable stack. New blocks of memory are allocated on the local variable stack with each subroutine call, creating working storage for the subroutine. Even if only registers are used to hold temporary values within the subroutine, a local variable stack of some sort is required to save register values of the calling routine before they are destroyed.

The local variable stack not only allows reentrancy and recursion, but it can also save memory. In subroutines with statically allocated local variables, the variables take up space whether the subroutine is active or not. With a local variable stack, space on the stack is reused as subroutines are called and the stack depth increases and decreases.

1.4.4 The parameter stack

The final common use for a stack in computing is as a subroutine parameter stack. Whenever a subroutine is called it must usually be given a set of parameters upon which to act. Those parameters may be passed by placing values in registers, which has the disadvantage of limiting the possible number of parameters. The parameters may also be passed by copying them or pointers to them into a list in the calling routine's memory. In this case, reentrancy and recursion may not be possible. The most flexible method is to simply copy the elements onto a parameter stack before performing a procedure call. The parameter stack allows both recursion and reentrancy in programs.

1.4.5 Combination stacks

Real machines combine the various stack types. It is common in register-based machines to see the local variable stack, parameter stack, and return address stack combined into a single stack of activation records, or "frames." In these machines, expression evaluation stacks are eliminated by the compiler, and instead registers are allocated to perform expression evaluation.

The approach taken by the stack machines described later in this book is to have separate hardware expression evaluation and return stacks. The expression evaluation stacks are also used for parameter passing and local variable storage. Sometimes, especially when conventional languages such as C or Pascal are being executed, a frame pointer register is used to store local variables in an area of program memory. " -- http://users.ece.cmu.edu/~koopman/stack_computers/sec1_4.html

" ...nesting of tasks or threads. The task and its creator share the stack frames that existed at the time of task creation, but not the creator's subsequent frames nor the task's own frames. This was supported by a cactus stack, whose layout diagram resembled the trunk and arms of a Saguaro cactus. Each task had its own memory segment holding its stack and the frames that it owns. The base of this stack is linked to the middle of its creator's stack. " -- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stack_machine (see also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spaghetti_stack , another name for the same concept)

" Use in programming language runtimes

The term spaghetti stack is closely associated with implementations of programming languages that support continuations. Spaghetti stacks are used to implement the actual run-time stack containing variable bindings and other environmental features. When continuations must be supported, a function's local variables cannot be destroyed when that function returns: a saved continuation may later re-enter into that function, and will expect not only the variables there to be intact, but it will also expect the entire stack to be present so the function is able to return again. To resolve this problem, stack frames can be dynamically allocated in a spaghetti stack structure, and simply left behind to be garbage collected when no continuations refer to them any longer. This type of structure also solves both the upward and downward funarg problems, so first-class lexical closures are readily implemented in that substrate also. " -- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spaghetti_stack

Some VMs with stack-based (as opposed to register-based) instructions have a value stack (for the VM instructions), a call stack, and a block stack (to keep track of eg that you are in a FOR loop nested inside another FOR loop; a BREAK would pop this stack); for example, Python [16].

In many architectures the stack grows downwards [17] [18] [19], eg x86, Mostek6502, PDP11, most MIPS ABIs [20] [21] [22].

In early memory-constrained devices, often there is either just a memory section for program code, and a section for data, and a stack, and the code is placed near location 0, then the data section, whereas the stack is placed in high memory (near the largest addresses) and grows down [23].

Memory-constrained devices often don't have a heap that grows (only a fixed-size data section, which can be thought of as a fixed-size heap), which means that often the only memory section with a dynamically changing size is the stack. [24]

This arrangement would also work if the fixed-size data were placed in high memory and the stack were placed in low memory and grew up. This is seen sometimes (eg HP PA-RISC, Multics [25]) but less frequently.

One reason given for the stack being placed in high memory and growing downwards is that if the ISA makes it more efficient to add only UNSIGNED (always positives) offsets to memory addresses, then since a common calculation is to add an offset to the stack pointer to locate something in the stack, this will be most efficient if that offset is always positive, that is, if the stack pointer points to the lowest memory location in the stack, which occurs if the stack grows downwards [26] [27]. In addition, alignment calculations are simpler; eg "If you place a local variable on the stack which must be placed on a 4-byte boundary, you can simply subtract the size of the object from the stack pointer, and then zero out the two lower bits to get a properly aligned address. If the stack grows upwards, ensuring alignment becomes a bit trickier." [28].

Elsewhere, we treat (todo):

Links:

There are three basic ways to implement regular expressions:

It is also possible to try to use one of these techniques and then fall back to another one in certain cases, or to partially combine the first two techniques via simulating the NFA but with caching [32].

grep, awk, tcl use combinations of the first two techniques. Perl, PCRE, Python, Ruby, and Java use the third technique [33].

A popular C library to implement (extended) regular expressions is PCRE.

Links:

Links:

http://gleichmann.wordpress.com/2011/01/09/functional-scala-turning-methods-into-functions/

note: i think eta is more than that:

SL Peyton Jones, Compiling Haskell by program transformation: a report from the trenches says it is when you have something of the form f = \x -> blah in \y -> blah2, and you notice that f is always applied to two arguments, so you transform it to f = \x y -> blah3.

Lenient evaluation is neither strict nor lazy citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.137.9885 by G Tremblay - 2000 - Cited by 2 - Related articles

4.4. Combinator parsing An interesting approach to building parsers in functional languages, described in [29,30], is called combinator parsing . In this approach, a parser is de3ned as a function which, from a string, produces a list of possible results together with the unconsumed part of the input; various combining forms (higher-order functions = combinators) are then used to combine parsers in ways which mimic the di1erent grammar constructs, e.g., sequencing, choice, repetition. For example, suppose we have some parsers p1 and p2 which recognize, respectively, the non- terminals t 1 and t 2 . Then, the parser that recognizes t 1

← p1 inp; (v2, out2) ← p2 out1] Here, laziness is required because of the way repetition is handled: given a parser p that recognizes the non-terminal t , t ∗ would be recognized by many p de3ned as follows [30]: G. Tremblay/Computer Languages 26 (2000) 43–66 59 > many p >

> ‘alt’ > (succeed []) In function many , one of the subexpression appearing as an argument expression is a call made to many p ; this is bound to create an in3nite loop in a language not using call-by-need, which is e1ectively what happens when such combinator parsers are translated directly into a strict language such as SML or a non-strict language such as Id . Instead, in a non-lazy language, eta -abstraction would need to be used or explicit continuations would have to be manipulated in order to handle backtracking [31].

Links:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Threaded_code

" Separating the data and return stacks in a machine eliminates a great deal of stack management code, substantially reducing the size of the threaded code. The dual-stack principle was originated three times independently: for Burroughs large systems, Forth and PostScript?, and is used in some Java virtual machines.

Three registers are often present in a threaded virtual machine. Another one exists for passing data between subroutines ('words'). These are:

ip or i (instruction pointer) of the virtual machine (not to be confused with the program counter of the underlying hardware implementing the VM)

w (work pointer)

rp or r (return stack pointer)

sp or s (parameter stack pointer for passing parameters between words)Often, threaded virtual machines such as implementations of Forth have a simple virtual machine at heart, consisting of three primitives. Those are:

nest, also called docol

unnest, or semi_s (;s)

nextIn an indirect-threaded virtual machine, the one given here, the operations are:

next: *ip++ -> w ; jmp w++ nest: ip -> *rp++ ; w -> ip ; next unnest: *--rp -> ip ; next

This is perhaps the simplest and fastest interpreter or virtual machine. " -- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Threaded_code

(note: 'nest' is CALL, and 'unnest' is RETURN (or EXIT))

AST walking (tree walking) vs tree grammars:

http://www.antlr3.org/pipermail/antlr-interest/2011-February/040686.html

Translators Should Use Tree Grammars : http://web.archive.org/web/20121114144133/http://www.antlr.org/article/1100569809276/use.tree.grammars.tml

Manual Tree Walking Is Better Than Tree Grammars: http://www.antlr2.org/article/1170602723163/treewalkers.html

conversion between languages: http://web.archive.org/web/20090611075009/http://jazillian.com/howC.html

http://web.archive.org/web/20070210070048/http://www.jazillian.com/how.html

http://www.nicklib.com/application/3001

todo:

---

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Setjmp.h

common compiler targets:

stack based, accumulator-based, register-based

finite registers (actual assembly languages) vs. infinite (LLVM)

the basic steps (typically):

examples of some things that might have to be expanded or recognized:

The output of liveness analysis is (a) a table that for each variable, describes the region(s) of code in which space for that variable must be allocated, and (b) an interference graph, whose nodes are variables and where there is an edge between two variables if they cannot be allocated in the same memory location (because their scopes overlap).

Naive solution: assume every variable must be allocated at the beginning of the program and is never reclaimed until the end of the program. The problem with this is that many (often, the vast majority) of variables are only needed for a very short while for storing intermediate results, so by allocating space for all of them throughout the entire program you vastly increase the memory used by the program beyond what is actually required.

http://www.montefiore.ulg.ac.be/~geurts/Cours/compil/2014/06-finalcode-2014-2015.pdf describes an algorithm for register allocation.

(for register machines)

The output of register allocation is a table that for each variable, describes in which register that variable is allocated; and if not all variables can be stored in registers, which ones must be 'spilled' to other places. Register allocation can be run separately for each procedure.

Naive solution: store everything on the heap (in main memory). The problem with this is that you are constantly issuing load instructions before each use of a variable and store instructions after each assignment of a variable. For intermediate results that are used immediately after they are generated, or soon after, this is very inefficient, because the latency of accessing main memory can be orders of magnitude higher than accessing registers.

http://www.montefiore.ulg.ac.be/~geurts/Cours/compil/2014/06-finalcode-2014-2015.pdf describes an algorithm for register allocation.

What 'other places' are available?

Links:

links:

"Linear Scan Register Allocation" see https://synrc.com/publications/cat/Functional%20Languages/AliceML/christian_mueller_diplom.pdf section 1.3

see also JVM verification

Links:

implementing libraries, data structures, algorithms:

jlouis 8 hours ago

Something you may find interesting is that the new faster maps are loosely based on Rich Hickey's HAMT implementation that is used in Clojure. Jose and co. in Elixir adapted/is-adapting their internals to use maps as well, as they were faster than any implementation they had.

In addition, I wrote a full QuickCheck? model for the new maps. That is, we randomly generate unit test cases for the maps and verify them. We have generated several millions of those test cases, including variants which heavily collides on the hash. This weeded out at least 10 grave bugs from the implementation, which in turn means this release is probably very stable with respect to maps.

reply

pselbert 1 hour ago

Some great articles about the process of "Breaking Erlang Maps" via QuickCheck?. Thanks for those!

1: https://medium.com/@jlouis666/breaking-erlang-maps-1-31952b8...

2: https://medium.com/@jlouis666/breaking-erlang-maps-2-362730a...

reply

There are some optimizations that you would think would be negligable when applied to real programs; these are often very useful when applied to machine-generated code eg code generated by intermediate compiler passes ("most of the cases where they kick in are in code coming from macro instantiation, inlining, and other abstraction-elimination activities the compiler performs. The reality is that humans don't commonly write such silly things directly." -- [36])

"

Runtime Library

Rarely mentioned, but critical, is the need to write a runtime library. This is a major project. It will serve as a demonstration of how the language features work, so it had better be good. Some critical things to get right include:

I/O performance. Most programs spend a lot of time in I/O. Slow I/O will make the whole language look bad. The benchmark is C stdio. If the language has elegant, lovely I/O APIs, but runs at only half the speed of C I/O, then it just isn't going to be attractive.

Memory allocation. A high percentage of time in most programs is spent doing mundane memory allocation. Get this wrong at your peril.

Transcendental functions. OK, I lied. Nobody cares about the accuracy of transcendental functions, they only care about their speed. My proof comes from trying to port the D runtime library to different platforms, and discovering that the underlying C transcendental functions often fail the accuracy tests in the D library test suite. C library functions also often do a poor job handling the arcana of the IEEE floating-point bestiary — NaNs, infinities, subnormals, negative 0, etc. In D, we compensated by implementing the transcendental functions ourselves. Transcendental floating-point code is pretty tricky and arcane to write, so I'd recommend finding an existing library you can license and adapting that." -- So You Want To Write Your Own Language? By Walter Bright---

" Lowering

One semantic technique that is obvious in hindsight (but took Andrei Alexandrescu to point out to me) is called "lowering." It consists of, internally, rewriting more complex semantic constructs in terms of simpler ones. For example, while loops and foreach loops can be rewritten in terms of for loops. Then, the rest of the code only has to deal with for loops. This turned out to uncover a couple of latent bugs in how while loops were implemented in D, and so was a nice win. It's also used to rewrite scope guard statements in terms of try-finally statements, etc. Every case where this can be found in the semantic processing will be win for the implementation.

If it turns out that there are some special-case rules in the language that prevent this "lowering" rewriting, it might be a good idea to go back and revisit the language design.

Any time you can find commonality in the handling of semantic constructs, it's an opportunity to reduce implementation effort and bugs. " -- So You Want To Write Your Own Language? By Walter Bright

---

" error messages are a big factor in the quality of implementation of the language. It's what the user sees, after all. If you're tempted to put out error messages like "bad syntax," perhaps you should consider taking up a career as a chartered accountant instead of writing a language. Good error messages are surprisingly hard to write, and often, you won't discover how bad the error messages are until you work the tech support emails.

The philosophies of error message handling are:

Print the first message and quit. This is, of course, the simplest approach, and it works surprisingly well. Most compilers' follow-on messages are so bad that the practical programmer ignores all but the first one anyway. The holy grail is to find all the actual errors in one compile pass, leading to:

Guess what the programmer intended, repair the syntax trees, and continue. This is an ever-popular approach. I've tried it indefatigably for decades, and it's just been a miserable failure. The compiler seems to always guess wrong, and subsequent messages with the "fixed" syntax trees are just ludicrously wrong.

The poisoning approach. This is much like how floating-point NaNs are handled. Any operation with a NaN operand silently results in a NaN. Applying this to error recovery, and any constructs that have a leaf for which an error occurred, is itself considered erroneous (but no additional error messages are emitted for it). Hence, the compiler is able to detect multiple errors as long as the errors are in sections of code with no dependency between them. This is the approach we've been using in the D compiler, and are very pleased with the results." -- So You Want To Write Your Own Language? By Walter Bright---

"What else does the user care about in the hidden part of the compiler? Speed. I hear it over and over — compiler speed matters a lot....Wanna know the secret of making your compiler fast? Use a profiler. " -- So You Want To Write Your Own Language? By Walter Bright

---

"

Work

First off, you're in for a lot of work…years of work…most of which will be wandering in the desert. The odds of success are heavily stacked against you. If you are not strongly self-motivated to do this, it isn't going to happen. If you need validation and encouragement from others, it isn't going to happen.

Fortunately, embarking on such a project is not major dollar investment; it won't break you if you fail. Even if you do fail, depending on how far the project got, it can look pretty good on your résumé and be good for your career. " -- So You Want To Write Your Own Language? By Walter Bright

---

" Getting past the syntax, the meat of the language will be the semantic processing, which is where meaning is assigned to the syntactical constructs. This is where you'll be spending the vast bulk of design and implementation. It's much like the organs in your body — they are unseen and we don't think about them unless they are going wrong. There won't be a lot of glory in the semantic work, but in it will be the whole point of the language.

Once through the semantic phase, the compiler does optimizations and then code generation — collectively called the "back end." These two passes are very challenging and complicated. Personally, I love working with this stuff, and grumble that I've got to spend time on other issues. But unless you really like it, and it takes a fairly unhinged programmer to delight in the arcana of such things, I recommend taking the common sense approach and using an existing back end, such as the JVM, CLR, gcc, or LLVM. (Of course, I can always set you up with the glorious Digital Mars back end!) " -- So You Want To Write Your Own Language? By Walter Bright

---

" The first tool that beginning compiler writers often reach for is regex. Regex is just the wrong tool for lexing and parsing. Rob Pike explains why reasonably well. I'll close that with the famous quote from Jamie Zawinski:

"Some people, when confronted with a problem, think 'I know, I'll use regular expressions.' Now they have two problems."

Somewhat more controversial, I wouldn't bother wasting time with lexer or parser generators and other so-called "compiler compilers." They're a waste of time. Writing a lexer and parser is a tiny percentage of the job of writing a compiler. Using a generator will take up about as much time as writing one by hand, and it will marry you to the generator (which matters when porting the compiler to a new platform). And generators also have the unfortunate reputation of emitting lousy error messages. " -- So You Want To Write Your Own Language? By Walter Bright

---

Three strategies for code reuse via generics:

(todo: is that accurate? i am mainly trying to summarize part of http://cglab.ca/~abeinges/blah/rust-reuse-and-recycle/ )

Links:

Some object file formats and related formats are:

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_executable_file_formats for a longer list

Links:

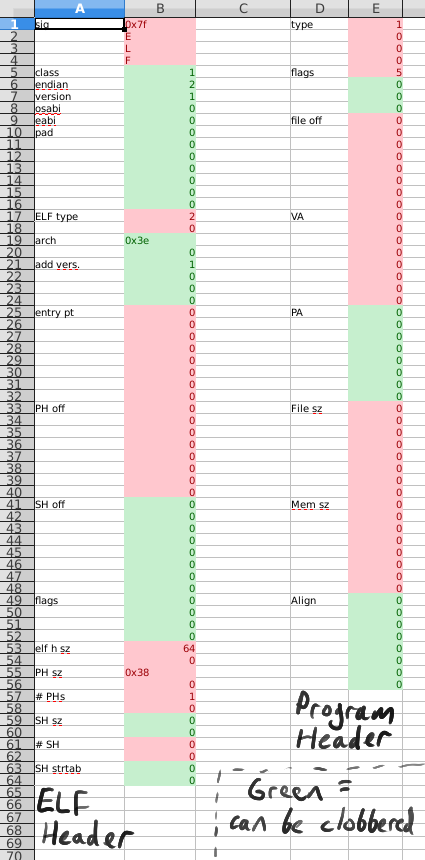

Minimal executables with ELF:

PE links:

Slim binaries / Semantic dictionary encoding:

Links:

---

zzzcpan 1 day ago [-]

Frankly, I don't see anything interesting in that list, especially for amateurs.

As an amateur compiler writer you would probably want to make something useful in a few weeks, not waste a year playing around. And it's a very different story. It's essentially about making a meta DSL, that compiles into another language and plays well with existing libraries, tooling, the whole ecosystem, but also does something special and useful for you. So, you should learn parsing, possibly recursive descend for the code and something else for expressions, a bit about working with ASTs and that's pretty much it.

reply

PaulHoule? 1 day ago [-]

Is amateur the right word?

I am in it for the money which I guess makes me a pro but I don't have a computer science background and frankly in 2016 I am afraid the average undergrad compiler course is part of the problem as much as the solution.

Another big issue is nontraditional compilers of many kinds such as js accelerators and things that compile to JavaScript?, domain specific languages, data flow systems, etc. Frankly I want to generate Java source or JVM byte code and could care less for real machine code.

reply

reymus 1 day ago [-]

"frankly in 2016 I am afraid the average undergrad compiler course is part of the problem as much as the solution."

What do you mean by that?

reply

tikhonj 1 day ago [-]

I'm not the OP, but I sympathize. The specific details covered in a "classical" compilers course are heavy weight and not super-relevant right now. These days you don't have to understand LR parsing or touch a parser-generator, you don't have to worry about register coloring... etc. Courses still use the Dragon Book which is older than I am and covers a bunch of stuff only relevant to writing compilers for C on resource-constrained systems.

Instead, I figure a course should cover basics of DSL design, types and type inference, working with ASTs, some static analysis and a few other things. That has some overlap with a traditional compilers course, but a pretty different focus.

reply

---

David "Kranz' diss is a Yale Computer Science Dept. tech report. I would say it is required reading for anyone interested in serious compiler technology for functional programming languages. You could probably order or download one from a web page at a url that I'd bet begins with http://www.cs.yale.edu/." -- [41]

David Kranz. ORBIT: An Optimizing Compiler for Scheme. Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, February 1988. Research Report 632, Department of Computer Science.

---

" ...techniques like cdr coding serve to bring the average case of list access and construction down from their worst case behavior of generating massive heap fragmentation (and thus defeating caching and prefetching) towards the behavior of nicely caching sequential data layouts (classical arrays) typically via tree like structures or SRFI-101. While traditional linked list structures due to potential heap fragmentation provide potentially atrocious cache locality and this cripple the performance of modern cache accelerated machines, more modern datastructures can simultaneously provide the traditional cons list pattern while improving cache locality and thus performance characteristics. Guy Steele himself has even come out arguing this point. " [42]

---

"JIT engines are viciously complicated beasts" -- Nathaniel Smith

---

http://home.pipeline.com/~hbaker1/CheneyMTA.html

---

see also section 'Hash tables' in proj-plbook-plChStdLibraries.

---

" A quick way to judge a language implementation is by inspecting its string concatenation function. If concat is implemented as a realloc and memcpy, well, the upstairs lights probably aren’t set to full brightness. Behold, in MoarVM? strings are broken into strands, and strands can repeat without taking up more memory. So this expression:

"All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy" x 1000

Doesn’t make a thousand copies of the string, or even make a thousand pointers to the same string. " [43]

---

some papers on implementation of continuations:

(as of [45])

see also draft: [46]

---

on the implementation of expandable (segmented or continuous but copying) stacks:

" simonmar on Nov 7, 2013 [-]

Segmented stacks are better even if you have a relocatable stack. GHC switched from monolithic copy-the-whole-thing-to-grow-it to segmented stacks a while ago, and it was a big win. Not just because we waste less space, but because the GC knows when individual stack segments are dirty so that it doesn't need to traverse the whole stack. To avoid the thrashing issue we copy the top 1KB of the previous stack chunk into the new stack chunk when we allocate a new chunk. "

" mattgreenrocks on Nov 6, 2013 [-]

Disclaimer: not a language designer/implementer (yet).

Couldn't segmented stacks for async/await-style IO be simulated by swapping the stack out at every await? I mean copying out the registers and the raw stack to some heap location, then restoring them by reversing the process later.

(One problem I see is that it'd be slow when lots of IO operations are involved.)

pcwalton on Nov 6, 2013 [-]

Doesn't work if threads can have pointers into each other's stacks (which we'd like to support someday for fork/join parallelism). "

discussion on "Abandoning segmented stacks in Rust ":

" [–]julesjacobs 5 points 4 years ago*

I thought about this problem a long time ago and came up with the following scheme that does not require any virtual memory support:

You allocate 1 big stack per hardware thread. On context switch, you copy the current stack to a different area in memory, and you load 1 or a fixed number of stack frames from the new thread onto the stack and start executing. On stack underflow, you the next 1 or a fixed number of stack frames from the remaining stack, and so on. This scheme ensures that context switch is amortized O(1): each stack frame is copied at most 1 time from the big stack to a different area in memory and each stack frame is copied at most 1 time back from memory onto the big stack. Note that it is very important not to copy the whole suspended stack back to the big stack on context switch, since that would mean an unbounded amount of stack copying if you context switch back and forth repeatedly, which means that it would no longer be amortized O(1).

The neat thing is that it avoids all the problems described in this post. When no context switching is happening, there is zero overhead, since you're running on one of the big stacks. This also means that there is no problem with the FFI or LLVM intrinsics, since there is always enough stack space to run them. Yet because on a context switch you only copy the actually used portion of the big stack to memory, each green thread only uses as much memory as it actually needs.

Of course given that most processors do have virtual memory support and 64 bit have enough address space, a solution that uses virtual memory may be faster because it does not require copying. This scheme does have the advantage that it wastes no memory for suspended threads; a solution using virtual memory will still waste up to the page size per thread (generally 4 KB).

permalinkembedsavegive gold

[–]matthieum 18 points 4 years ago

This has been evoked, however there is a big issue: you are assuming relocatable objects.

So, notwithstanding the cost of actually detecting/copying which could be manageable, there is the issue of having a mechanism to update all pointers to "stack" elements when copying it to the heap, and back.

permalinkembedsaveparentgive gold

[–]pkhuong 2 points 4 years ago

That's the sort of question that the scheme (and smalltalk) people have been considering for a long time. Will Clinger's "Implementation Strategies for First-Class Continuations" summarises the classic ones. I think you're describing the Hieb-Dybvig-Bruggeman strategy for one-shot continuations (i.e. cooperative threads) used in Chez Scheme.

permalinkembedsaveparentgive gold" ---

" up vote 13 down vote accepted

There are a number of papers on different kinds of dispatch:

M. Anton Ertl and David Gregg, Optimizing Indirect Branch Prediction Accuracy in Virtual Machine Interpreters, in Proceedings of the ACM SIGPLAN 2003 Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation (PLDI 03), pp. 278-288, San Diego, California, June 2003.

M. Anton Ertl and David Gregg, The behaviour of efficient virtual machine interpreters on modern architectures, in Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Parallel Computing (Europar 2001), pp. 403-412, LNCS 2150, Manchester, August 2001.

An excellent summary is provided by Yunhe Shi in his PhD? thesis.

Also, someone discovered a new technique a few years ago which is valid ANSI C.

" [47]

---

Dispatch Techniques

http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~matz/dissertation/matzDissertation-latex2html/node6.html

---

random tips:

" Context-free grammars. What this really means is the code should be parsable without having to look things up in a symbol table. C++ is famously not a context-free grammar. A context-free grammar, besides making things a lot simpler, means that IDEs can do syntax highlighting without integrating most of a compiler front end. As a result, third-party tools become much more likely to exist. Redundancy. Yes, the grammar should be redundant. You've all heard people say that statement terminating ; are not necessary because the compiler can figure it out. That's true — but such non-redundancy makes for incomprehensible error messages. Consider a syntax with no redundancy: Any random sequence of characters would then be a valid program. No error messages are even possible. A good syntax needs redundancy in order to diagnose errors and give good error messages. "

"The first tool that beginning compiler writers often reach for is regex. Regex is just the wrong tool for lexing and parsing. Rob Pike explains why reasonably well."

" The philosophies of error message handling are:

Print the first message and quit. This is, of course, the simplest approach, and it works surprisingly well. Most compilers' follow-on messages are so bad that the practical programmer ignores all but the first one anyway. The holy grail is to find all the actual errors in one compile pass, leading to:

Guess what the programmer intended, repair the syntax trees, and continue. This is an ever-popular approach. I've tried it indefatigably for decades, and it's just been a miserable failure. The compiler seems to always guess wrong, and subsequent messages with the "fixed" syntax trees are just ludicrously wrong.

The poisoning approach. This is much like how floating-point NaNs are handled. Any operation with a NaN operand silently results in a NaN. Applying this to error recovery, and any constructs that have a leaf for which an error occurred, is itself considered erroneous (but no additional error messages are emitted for it). Hence, the compiler is able to detect multiple errors as long as the errors are in sections of code with no dependency between them. This is the approach we've been using in the D compiler, and are very pleased with the results."" Runtime Library

Rarely mentioned, but critical, is the need to write a runtime library. This is a major project. It will serve as a demonstration of how the language features work, so it had better be good. Some critical things to get right include:

I/O performance. Most programs spend a lot of time in I/O. Slow I/O will make the whole language look bad. The benchmark is C stdio. If the language has elegant, lovely I/O APIs, but runs at only half the speed of C I/O, then it just isn't going to be attractive.

Memory allocation. A high percentage of time in most programs is spent doing mundane memory allocation. Get this wrong at your peril.

Transcendental functions. OK, I lied. Nobody cares about the accuracy of transcendental functions, they only care about their speed. My proof comes from trying to port the D runtime library to different platforms, and discovering that the underlying C transcendental functions often fail the accuracy tests in the D library test suite. C library functions also often do a poor job handling the arcana of the IEEE floating-point bestiary — NaNs, infinities, subnormals, negative 0, etc. In D, we compensated by implementing the transcendental functions ourselves. Transcendental floating-point code is pretty tricky and arcane to write, so I'd recommend finding an existing library you can license and adapting that.

A common trap people fall into with standard libraries is filling them up with trivia. Trivia is sand clogging the gears and just dead weight that has to be carried around forever. My general rule is if the explanation for what the function does is more lines than the implementation code, then the function is likely trivia and should be booted out."" String I/O should be unicode-aware & support utf-8. Binary I/O should exist. Console I/O is nice, and you should support it if only for the sake of having a REPL with readline-like features. Basically all of this can be done by making your built-in functions wrappers around the appropriate safe I/O functions from whatever language you’re building on top of (even C, although I wouldn’t recommend it). It’s no longer acceptable to expect strings to be zero-terminated rather than length-prefixed. It’s no longer acceptable to have strings default to ascii encoding instead of unicode. In addition to supporting unicode strings, you should also probably support byte strings, something like a list or array (preferably with nesting), and dictionaries/associative arrays. It’s okay to make your list type do double-duty as your stack and queue types and to make dictionaries act as classes and objects. Good support for ranges/spans on lists and strings is very useful. If you expect your language to do string processing, built-in regex is important. If you provide support for parallelism that’s easier to manage than mutexes, your developers will thank you. While implicit parallelism can be hard to implement in imperative languages (much easier in functional or pure-OO languages), even providing support for thread pools, a parallel map/apply function, or piping data between independent threads (like in goroutines or the unix shell) would help lower the bar for parallelism support. Make sure you have good support for importing third party packages/modules, both in your language and in some other language. Compiled languages should make it easy to write extensions in C (and you’ll probably be writing most of your built-ins this way anyway). If you’re writing your interpreted language in another interpreted language (as I did with Mycroft) then make sure you expose some facility to add built-in functions in that language. For any interpreted language, a REPL with a good built-in online help system is a must. Users who can’t even try out your language without a lot of effort will be resistant to using it at all, whereas a simple built-in help system can turn exploration of a new language into an adventure. Any documentation you have written for core or built-in features (including documentation on internal behavior) should be assessible from the REPL. This is easy to implement (see Mycroft’s implementation of online help) and is at least as useful for the harried language developer as for the new user. "

---

todo put this somewhere (mainly for the tips at the top of the file):

---

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Man_or_boy_test

---

"

jchw 11 hours ago [–]

Something that surprised me: Compilers happily optimize pointer to member function calls out if it knows definitely what the pointer points to, but not if the pointer is to a virtual function. Recently figured that out thanks to a slightly related debate on whether it would optimize the first case at all - which I thought it would - but I’m surprised by the second case, since it’s not like there’s a virtual dispatch to worry about once you’ve already taken a reference - you’re already specifying exactly which one implementation you want. Just one of many nuggets learned from Godbolt: apparently marking a function virtual can kill optimizations even in cases where it seems like it shouldn’t.

reply

KMag 10 hours ago [–]

Where's your point of confusion? There's still virtual dispatch going on with a pointer to virtual member function... they're typically implemented as fat pointers containing the vtable offset, and calling via the pointer still does virtual dispatch.

An alternative would be for the compiler to generate a stub function (can be shared across all classes for cases where the same vtable offset is used, unless your architecture has some very exotic calling convention) that jumps to a fixed offset in the vitable, and use a skinny pointer to that stub as a virtual member function pointer, but that's not the usual implementation.

In any case, calling through a pointer to virtual member function has to perform virtual dispatch unless the compiler can statically constrain the runtime type of *this being used at the call site. Remember that C++ needs to allow separate compilation, so without a full-program optimizer that breaks dlopen(), C++ can't perform devirtualization on non-final classes.

Making the class final will allow the compiler to statically constrain the runtime type and devirtualize the pointer to member function call.

Edit: added paragraph break.

reply

jchw 8 hours ago [–]

Ahhh, nevermind. I was under the impression that when you grabbed a pointer to member function, it was grabbing a specific implementation. I actually did not know it supported virtual dispatch.

Now I think I finally understand why MSVC pointer to member functions are 16 bytes wide; I knew about the multi-inheritance this pointer adjustment, but I actually had no idea about virtual dispatch through member pointers. Frankly, I never used them in a way that would’ve mattered for this.

reply "

---

---

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persistent_data_structure

---

" One neat trick I pulled from otcc is the symbol patching mechanism. Namely, when we don't know the value of a given symbol yet while emitting code we use the bits dedicated to this value in the machine code to store a linked list of all locations to be patched with the given symbol value. See the code of the patch function for details about that. " -- [51]

---

A language for describing ASTs. Software is available to autogenerate code that implements ASTs described by ASDL.

Used in Python and in Oil shell.

See [[plChDataLangs.txt?]] for more details.

---

https://engineering.mongodb.com/post/transpiling-between-any-programming-languages-part-1

---

The Implementation of Lua5.0 section 5 "Functions and Closures" describes a simple implementation of closures using indirect pointers called 'upvalues'.

[52] recommends this "Responsive compilers" talk at PLISS 2019, saying "In that talk he also provided some examples of how the Rust language was accidentally mis-designed for responsive compilation. It is an entirely watchable talk about compiler engineering and I recommend checking it out." slides: https://nikomatsakis.github.io/pliss-2019/responsive-compilers.html#1

in the talk, Matsakis suggests using the Salsa framework (spreadsheet-y updates; "a Rust framework for writing incremental, on-demand programs -- these are programs that want to adapt to changes in their inputs, continuously producing a new output that is up-to-date").

guides on implementing type checkers and type inference:

links for optimization/static analysis etc:

mb:

learning projects that document their learning:

misc:

" Graydon Hoare: 21 compilers and 3 orders of magnitude in 60 minutes

In 2019, Graydon Hoare gave a talk to undergraduates (PDF of slides) trying to communicate a sense of what compilers looked like from the perspective of people who did it for a living.

I've been aware of this talk for over a year and meant to submit a story here, but was overcome by the sheer number of excellent observations. I'll just summarise the groups he uses:

The giants: by which he means the big compilers that are built the old-fashioned way that throw massive resources at attaining efficiency

The variants, which use tricks to avoid being so massive:

Fewer optimisations: be traditional, but be selective and only the optimisations that really pay off

Use compiler-friendly languages, by which he is really taking about languages that are good for implementing compilers, like Lisp and ML

Theory-driven meta-languages, esp. how something like yacc allows a traditional Dragon-book style compiler to be written more easily

Base compiler on a carefully designed IR that is either easy to compile or reasonable to bytecode-interpret

Exercise discretion to have the object code be a mix of compiled and interpreted

Use sophisticated partial evaluation

Forget tradition and implement everything directly by hand I really recommend spending time working through these slides. While much of the material I was familiar with, enough was new, and I really appreciated the well-made points, shout-outs to projects that deserve more visibility, such as Nanopass compilers and CakeML?, and the presentation of the Futamura projections, a famously tricky concept, at the undergraduate level. By Charles Stewart at 2022-02-27 14:47

| Implementation | other blogs | 51627 reads |

" -- [56]

might need a large stack when calling into the kernel:

---

on implementing an expression evaluator with automatic memory-management with C++

" You don’t need to use the built in shared pointer type, which is generic and so not optimised for various cases, to write idiomatic and clean C++. You write a LispValue? class that is a tagged union of either a pointer to some rich structure or an embedded value. Most Lisp implementations use tagging on the low bit, with modern CPUs and addressing modes it’s useful to use 0 to indicate an integer and 1 to indicate a pointer because the subtract 1 can be folded into other immediate offsets for field or vtable addressing. If the value is a pointer, the pointee exposes non-virtual refcount manipulation operations in the base class. Your value type calls these in its copy constructor and copy assignment operator. For move assignment or move construction, your value type simply transfers ownership and zeroes out the original. In its destructor, you drop the ref count. When the refcount reaches zero, it calls a virtual function which can call the destructor, put the object back into a pool, or do anything else.

Implemented like this, you have no virtual calls for refcount manipulation and so all of your refcount operations are inlined. All refcount operations are in a single place, so you can switch between atomic and non atomic ops depending on whether you want to support multiple threads. More importantly, it is now impossible by construction to have mismatched refcount operations. Any copy of the value object implicitly increments the refcount of the object that it refers to, any time one is dropped, it does the converse. Now you can store LipsValues? in any C++ collection and have memory management just work. " -- david chisnall

---

https://carolchen.me/blog/jits-intro/ https://carolchen.me/blog/jits-impls/

Chapter ?: Parsing (and lexing) Chapter ?: targets, IRs, VMs and runtimes Chapter ?: Interop Chapter ?: Hard things to make it easy for the programmer (contains: garbage collection, greenthreads, TCO and strictness analysis) Chapter ?: Tradeoffs * contains: Constraints that performance considerations of the language and the toolchain impose on language design