![[Home]](http://www.bayleshanks.com/cartoonbayle.png)

Difference between revision 17 and current revision

No diff available." The following registers are required for a virtual Forth computer:

Forth Register 8086 Register Function IP SI Interpreter Pointer SP SP Data Stack Pointer RP RP Return Stack Pointer WP AX Word or Work Pointer UP (in memory) User Area Pointer

...

eForth Kernel

System interface:BYE, ?rx, tx!, !io Inner interpreters: doLIT, doLIST, next, ?branch, branch, EXECUTE, EXIT Memory access: ! , @, C!, C@ Return stack: RP@, RP!, R>, R@, R> Data stack: SP@, SP!, DROP, DUP, SWAP, OVER Logic: 0<, AND, OR, XOR Arithmetic: UM+ " -- http://www.exemark.com/FORTH/eForthOverviewv5.pdf

---

here are CamelForth?'s ~70 Primitives:

http://www.bradrodriguez.com/papers/glosslo.txt

design rationale for this choice:

" 1. Fundamental arithmetic, logic, and memory operators are CODE. 2. If a word can't be easily or efficiently written (or written at all) in terms of other Forth words, it should be CODE (e.g., U<, RSHIFT). 3. If a simple word is used frequently, CODE may be worthwhile (e.g., NIP, TUCK). 4. If a word requires fewer bytes when written in CODE, do so (a rule I learned from Charles Curley). 5. If the processor includes instruction support for a word's function, put it in CODE (e.g. CMOVE or SCAN on a Z80 or 8086). 6. If a word juggles many parameters on the stack, but has relatively simple logic, it may be better in CODE, where the parameters can be kept in registers. 7. If the logic or control flow of a word is complex, it's probably better in high-level Forth. " -- http://www.bradrodriguez.com/papers/moving5.htm

ANS Forth Core wordsThese are required words whose definitions are specified by the ANS Forth document.

! x a-addr -- store cell in memory + n1/u1 n2/u2 -- n3/u3 add n1+n2 +! n/u a-addr -- add cell to memory

> n1 n2 -- flag test n1>n2, signed >R x -- R: -- x push to return stack ?DUP x -- 0

| x x DUP if nonzero |

ANS Forth ExtensionsThese are optional words whose definitions are specified by the ANS Forth document.

<> x1 x2 -- flag test not equal BYE i*x -- return to CP/M CMOVE c-addr1 c-addr2 u -- move from bottom CMOVE> c-addr1 c-addr2 u -- move from top KEY? -- flag return true if char waiting M+ d1 n -- d2 add single to double NIP x1 x2 -- x2 per stack diagram TUCK x1 x2 -- x2 x1 x2 per stack diagram U> u1 u2 -- flag test u1>u2, unsigned

Private ExtensionsThese are words which are unique to CamelForth?. Many of these are necessary to implement ANS Forth words, but are not specified by the ANS document. Others are functions I find useful.

(do) n1

| u1 n2 | u2 -- R: -- sys1 sys2 |

run-time code for DO(loop) R: sys1 sys2 --

| sys1 sys2 |

run-time code for LOOP(+loop) n -- R: sys1 sys2 --

| sys1 sys2 |

run-time code for +LOOP>< x1 -- x2 swap bytes ?branch x -- branch if TOS zero BDOS DE C -- A call CP/M BDOS branch -- branch always lit -- x fetch inline literal to stack PC! c p-addr -- output char to port PC@ p-addr -- c input char from port RP! a-addr -- set return stack pointer RP@ -- a-addr get return stack pointer SCAN c-addr1 u1 c -- c-addr2 u2 find matching char SKIP c-addr1 u1 c -- c-addr2 u2 skip matching chars SP! a-addr -- set data stack pointer SP@ -- a-addr get data stack pointer S= c-addr1 c-addr2 u -- n string compare n<0: s1<s2, n=0: s1=s2, n>0: s1>s2 USER n -- define user variable 'n' "

http://www.forthworks.com/retro https://forthworks.com/retro http://forthworks.com/retro/book.html http://forth.works/doc.html http://retroforth.org/Handbook-Latest.txt

The following notes are about Retro version 12.

Retro can be built in a reduced memory configuration that requires only 96KiB? memory (~70KiB? for the image, 0.5KiB? data stack, 1KiB? address stack, ~24KiB? remaining RAM available for use by the VM).

By contrast, "The standard system is configured with a very deep data stack (around 2,000 items) and an address stack that is 3x deeper." [1]

Much of this section is copied from http://forthworks.com/retro/book.html

Input is divided into a series of whitespace delimited tokens. Each of these is then processed individually. There are no parsing words in RETRO.

Tokens may have a single character prefix, which RETRO will use to decide how to process the token.

The major prefixes are: Prefix Used For @ Fetch from variable ! Store into variable & Pointer to named item

Comments are delimited by ().

Constant literals:

Data types used in Retro's stack notation (provided via comments in many word definitions):

To add words (which are Forth's equivalent to functions) to the "dictionary", use the ':' prefix with the name of the word, then the word definition, then ';' to terminate, e.g.:

:palindrome dup s:reverse s:eq? ;

Most Retro code is written using a literate file format called Unu, in which only code within ~~~-delimited blocks is executed. Unu has #-style headings: "# This is a heading".

" Strings in RETRO are NULL terminated sequences of values representing characters. Being NULL terminated, they can’t contain a NULL (ASCII 0).

The character words in RETRO are built around ASCII, but strings can contain UTF8 encoded data if the host platform allows. Words like s:length will return the number of bytes, not the number of logical characters in this case.

...

Some RETRO systems include support for floating point numbers. When present, this is built over the system libm using the C double type. ... Floating point values exist on a separate stack, and are bigger than the standard memory cells, so can not be directly stored and fetched from memory.

The floating point system also provides an alternate stack that can be used to temporarily store values. ... Floating point words are in the f: namespace. There is also a related e: namespace for encoded values, which allows storing of floats in standard memory. ... A combinator is a function that consumes functions as input. They are used heavily by the RETRO system. " -- http://forthworks.com/retro/book.html

" Words are grouped into broad namespaces by attaching a short prefix string to the start of a name.

The common namespaces are:

Prefix Contains

The "Glossary" is the (documentation of the?) standard library. It can be browsed online at http://forthworks.com:9999/

The words that i noticed mentioned in http://forthworks.com/retro/book.html are (much of the following is copied from there):

Combinators:

Stack ops:

Arrays:

Buffers:

Simple linear LIFO buffer. RETRO provides words for operating on a linear memory area. This can be useful in building strings or custom data structures.

A buffer is a linear sequence of memory. The buffer words provide a means of incrementally storing and retrieving values from it. The buffer words keep track of the start and end of the buffer. They also ensure that an ASCII:NULL is written after the last value, which make using them for string data easy.

Only one buffer can be active at a time. RETRO provides a buffer:preserve combinator to allow using a second one before returning to the prior one.

Example: 'Test d:create #1025 allot &Test buffer:set #100 buffer:add buffer:get n:put nl

(note: i think n:put prints numeric data, and nl prints newline)

Characters:

The Dictionary:

The Dictionary is a linked list containing the dictionary headers.

'Dictionary' is a variable holding a pointer to the most recent header.

Dictionary Header Structure (may change in future) Offset Contains

--------------------------- 0000 Link to Prior Header 0001 Link to XT 0002 Link to Class Handler 0003+ Word name (null terminated)

Don't use that structure directly; use the accessor words (see below).

Floating point:

Numbers in RETRO are signed, 32 bit integers with a range of -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647.

Pointers:

Variables:

Strings:

At the interpreter, strings get allocated in a rotating buffer. If you need to keep them around, use s:keep or s:copy to move them to more permanent storage. In a definition, the string is compiled inline and so is in permanent memory.

Strings are mutable.

Printing output:

Memory:

Conventions for word naming : predicates end with '?'. Spread data flow combinators end with '*'. Apply data flow combinators end with '@'.

" Example

{{ 'A var :++A &A v:inc ; ---reveal--- :B ++A ++A @A n:put nl ; }}

In this example, the lexical namespace is created with {{. A variable (A) and word (++A) are defined. Then a marker is set with ---reveal---. Another word (B) is defined, and the lexical area is closed with }}.

The headers between {{ and ---reveal--- are then hidden from the dictionary, leaving only the headers between ---reveal--- and }} exposed. Notes

This only affects word visibility within the scoped area. As an example:

:a #1 ;

{{ :a #2 ; ---reveal--- :b 'a s:evaluate n:put ; }}

In this, after }} closes the area, the :a #2 ; is hidden and the s:evaluate will find the :a #1 ; when b is run. " -- http://forthworks.com/retro/book.html

"...temporary strings are allocated in a rotating buffer." -- http://forthworks.com/retro/book.html

" Primitives

These are words that map directly to Nga instructions.

dup drop swap call eq? -eq? lt? gt? fetch store + - * /mod and or xor shift push pop 0;

Memory

fetch-next store-next , s,

Strings

s:to-number s:eq? s:length

Flow Control

choose if -if repeat again

Compiler & Interpreter

Compiler Heap ; [ ] Dictionary d:link d:class d:xt d:name d:add-header class:word class:primitive class:data class:macro prefix:: prefix:# prefix:& prefix:$ interpret d:lookup err:notfound

I could slightly reduce this. The $ prefix could be defined in higher level code, and I don’t strictly need to expose the fetch-next and store-next here. But since the are already implemented as dependencies of the words in the kernel, it would be a bit wasteful to redefine them later in higher level code.

With these words the rest of the language can be built up. Note that the Rx kernel does not provide any I/O words. It’s assumed that the RETRO interfaces will add these as best suited for the systems they run on. " -- http://forthworks.com/retro/book.html

The words that are not described or obvious from the above are:

" There is another small bit. All images start with a few key pointers in fixed offsets of memory. These are:

| Offset | Contains |

| ------ | --------------------------- |

| 0 | lit call nop nop |

| 1 | Pointer to main entry point |

| 2 | Dictionary |

| 3 | Heap |

| 4 | RETRO version identifier |

An interface can use the dictionary pointer and knowledge of the dictionary format for a specific RETRO version to identify the location of essential words like interpret and err:notfound when implementing the user facing interface. " -- http://forthworks.com/retro/book.html

" I’ve been pleased with Nga. On its own it really isn’t useful though. So with RETRO I embed it into a larger framework that adds some basic I/O functionality. The interfaces handle the details of passing tokens into the language and capturing any output. They are free to do this in whatever model makes most sense on a given platform.

So far I’ve implemented:

In all cases, the only common I/O word that has to map to an exposed instruction is putc, to display a single character to some output device. There is no requirement for a traditional keyboard input model.

By doing this I was able to solve the biggest portability issue with the RETRO 10/11 model (...RETRO 11 and the Ngaro VM assumed the existence of a console environment. All input was required to be input at the keyboard, and all output was to be shown on screen...), and make a much simpler, cleaner language in the end. " -- http://forthworks.com/retro/book.html

" RETRO does only minimal error checking. Non-Fatal

A non-fatal error will be reported on word not found during interactive or compile time. Note that this only applies to calls: if you try to get a pointer to an undefined word, the returned pointer will be zero. Fatal

A number of conditions are known to cause fatal errors. The main ones are stack overflow, stack underflow, and division by zero.

On these, RETRO will generally exit. For stack depth issues, the VM will attempt to display an error prior to exiting.

In some cases, the VM may get stuck in an endless loop. If this occurs, try using CTRL+C to kill the process, or kill it using whatever means your host system provides. Rationale

Error checks are useful, but slow - especially on a minimal system like RETRO. The overhead of doing depth or other checks adds up quickly.

As an example, adding a depth check to drop increases the time to use it 250,000 times in a loop from 0.16 seconds to 1.69 seconds. " -- http://forthworks.com/retro/book.html

" Prefixes as a Language Element

A big change in RETRO 12 was the elimination of the traditional parser from the language. This was a sacrifice due to the lack of an I/O model. RETRO has no way to know how input is given to the interpret word, or whether anything else will ever be passed into it.

And so interpret operates only on the current token. The core language does not track what came before or attempt to guess at what might come in the future.

This leads into the prefixes. RETRO 11 had a complicated system for prefixes, with different types of prefixes for words that parsed ahead (e.g., strings) and words that operated on the current token (e.g., @). RETRO 12 eliminates all of these in favor of just having a single prefix model.

The first thing interpret does is look to see if the first character in a token matches a prefix: word. If it does, it passes the rest of the token as a string pointer to the prefix specific handler to deal with. If there is no valid prefix found, it tries to find it in the dictionary. Assuming that it finds the words, it passes the d:xt field to the handler that d:class points to. Otherwise it calls err:notfound.

This has an important implication: words can not reliably have names that start with a prefix character.

It also simplifies things. Anything that would normally parse becomes a prefix handler. So creating a new word? Use the : prefix. Strings? Use '. Pointers? Try &. And so on. E.g.,

In ANS

| In RETRO |

| :foo ... ; |

| &foo |

| :bar ... &foo ; |

| 'hello_world! |

If you are familiar with ColorForth?, prefixes are a similar idea to colors, but can be defined by the user as normal words.

After doing this for quite a while I rather like it. I can see why Chuck Moore eventually went towards ColorForth? as using color (or prefixes in my case) does simplify the implementation in many ways. " -- http://forthworks.com/retro/book.html

" The standard RETRO is not a good choice for applications needing to be highly secure. Runtime Checks

The RETRO system performs only minimal checks. It will not load an image larger than the max set at build time. And stack over/underflow are checked for as code executes.

The system does not attempt to validate anything else, it’s quite easy to crash. Isolation

The VM itself and the core code is self contained. Nga does not make use of malloc/free, and uses only standard system libraries. It’s possible for buffer overruns within the image (overwriting Nga code), but the RETRO image shouldn’t leak into the C portions.

I/O presents a bigger issue. Anything involving I/O, especially with the unix: words, may be a vector for attacks. " -- http://forthworks.com/retro/book.html

" Proven software techniques of forty years ago have yet to reach widespread use, in deference to the “latest and greatest” proprietary solutions of dubious value. ... The Retro philosophy is a simple alternative for those willing to make a clean break with legacy software. ... At first Retro will appeal to computer hobbyists and electronic engineers. Once the rough edges are smoothed out, it could catch on with ordinary folks who don’t like waiting five minutes just to check their email (not to mention the long hours of setup and maintenance). Game programmers who take their craft seriously may also be interested. ... I strive to avoid the extraneous. That applies even to proven technologies, if I don’t need them. If my computer isn’t set up for people to log in over the network, I don’t want security features; they just get in the way. ... The thousands of languages in existence all fall into a handful of archetypes: Assembler, LISP, FORTRAN and FORTH represent the earliest descendants of nearly all languages. I hesitate to name a definitive “object-oriented” language, and here’s why: Object-Oriented programming is just a technique, and any language will suffice, even Assembler. The complexites of fancy languages like Ada and C++ are a departure from reality – the reality of the actual physical machine. When it all boils down, even LISP, FORTRAN and FORTH are only extensions of the machine.

I chose FORTH as the “native tongue” of Retro. LISP, FORTRAN, and other languages can be efficiently implemented as extensions of FORTH, but the reverse isn’t so efficient. Theoretically all languages are equivalent, but when design time, compilation time, and complexity are accounted for, FORTH is most efficient. FORTH also translates most directly to the hardware. (In fact, FORTH has been implemented in hardware; these “stack machines” are extremely efficient.) FORTH is also the easiest language to implement from scratch - a major concern when you’re trying to make a clean break. So with simplicity in mind, FORTH was the obvious choice. ...

I’m perfectly happy working with text only, and I go to great lengths to avoid using the standard graphical environments, which have major problems: windows, pulldown menus, and mice. Windows can’t share the screen nicely; that idea is hopeless. Pulldowns are tedious. Mice get in the way of typing without reducing the need for it; all they give me is tendonitis. Their main use is for drawing.

Some of my favorite interfaces: Telix, Telegard BBS, Pine, Pico, Lynx, and ScreamTracker?. All “hotkey” interfaces where you press a key or two to perform an action. Usually the important commands are listed at the bottom of the screen, or at least on a help screen. The same principles apply to graphical interfaces: use the full screen, except for a status and menu area on one edge. Resist the temptation to clutter up the screen.

As for switching between programs, the Windows methods suck; the only thing worse is Unix job control (jobs, fg, and such). The Linux method is tolerable: Alt-Arrows, Alt-F1, Alt-F2, etc. Still, things could be better: F11 and F12 cycle back and forth through all open programs; Alt-F1 assigns the currently selected program to F1, and likewise for the other function keys. Programs just won’t use function keys - Control and Alt combinations are less awkward and easier to remember, besides. I’ll also want a “last channel” key and a “task list” key; maybe I’ll borrow those stupid Win95 keys. The Pause key will do like it says - pause the current program - and Ctrl-Pause (Break) will kill it.

One more thing: consistency. I like programs to look different so I can tell them apart, but the keys should be the same as much as possible. Keys should be configured in one place, for all programs. Finally, remember the most consistent interface, one of the few constants throughout the history of computing - the text screen and keyboard, and the teletypewriter before that. Don’t overlook it. " -- http://forthworks.com/retro/book.html

core words ('base words') (section 'noop' through 'hack'): https://github.com/jamesbowman/swapforth/blob/master/j1a/basewords.fs

https://excamera.com/sphinx/article-j1a-swapforth.html https://raw.githubusercontent.com/jamesbowman/swapforth/master/j1a/doc/j1a-reference.pdf

https://github.com/wolfgangj/okami

http://www.retroprogramming.com/2012/03/itsy-forth-1k-tiny-compiler.html http://www.retroprogramming.com/2012/04/itsy-forth-dictionary-and-inner.html http://www.retroprogramming.com/2012/04/itsy-forth-primitives.html http://www.retroprogramming.com/2012/06/itsy-forth-compiler.html

https://github.com/cesarblum/sectorforth

"sectorforth is a 16-bit x86 Forth that fits in a 512-byte boot sector.

Inspiration to write sectorforth came from a 1996 Usenet thread (in particular, Bernd Paysan's first post on the thread). Batteries not included

sectorforth contains only the eight primitives outlined in the Usenet post above, five variables for manipulating internal state, and two I/O primitives.

With that minimal set of building blocks, words for branching, compiling, manipulating the return stack, etc. can all be written in Forth itself (check out the examples!).

The colon compiler (:) is available, so new words can be defined easily (that means ; is also there, of course).

Contrary to many Forth implementations, sectorforth does not attempt to convert unknown words to numbers, since numbers can be produced using the available primitives. The two included I/O primitives are sufficient to write a more powerful interpreter that can parse numbers.

Primitives

Primitive Stack effects Description @ ( addr -- x ) Fetch memory contents at addr ! ( x addr -- ) Store x at addr sp@ ( -- sp ) Get pointer to top of data stack rp@ ( -- rp ) Get pointer to top of return stack 0= ( x -- flag ) -1 if top of stack is 0, 0 otherwise + ( x y -- z ) Sum the two numbers at the top of the stack nand ( x y -- z ) NAND the two numbers at the top of the stack exit ( r:addr -- ) Pop return stack and resume execution at addr key ( -- x ) Read key stroke as ASCII character emit ( x -- ) Print low byte of x as an ASCII character

Variables

Variable Description state 0: execute words; 1: compile word addresses to the dictionary tib Terminal input buffer, where input is parsed from >in Current parsing offset into terminal input buffer here Pointer to next free position in the dictionary latest Pointer to most recent dictionary entry "

"A FORTH in 422 bytes"

https://github.com/fuzzballcat/milliForth

" Word Signature Function @ ( addr -- value ) Get a value at an address ! ( value addr -- ) Store a value at an address sp@ ( -- sp ) Get pointer to top of the data stack rp@ ( -- rp ) Get pointer to top of the return stack 0= ( value -- flag ) Check if a value equals zero (-1 = TRUE, 0 = FALSE) + ( a b -- a+b ) Sum two numbers nand ( a b -- aNANDb ) NAND two numbers exit ( r:addr -- ) Pop from the return stack, resume execution at the popped address key ( -- key ) Read a keystroke emit ( char -- ) Print out an ASCII character state ( -- state ) The state of the interpreter (0 = compile words, 1 = execute words) >in ( -- >in ) The current offset into the terminal input buffer here ( -- here ) The pointer to the next available space in the dictionary latest ( -- latest ) The pointer to the most recent dictionary space

milliFORTH is effectively the same FORTH as implemented by sectorFORTH, with a few modifications:

Words don't get hidden while you are defining them. This doesn't really hinder your actual ability to write programs, but rather makes it possible to hang the interpreter if you do something wrong in this respect.

There's no tib (terminal input buffer) word, because tib always starts at 0x0000, so you can just use >in and don't need to add anything to it.

In the small (production) version, the delete key doesn't work. I think this is fair since sectorLISP doesn't handle backspace either; even if you add it back, milliFORTH is still smaller by a few bytes.

Error handling is even sparser. Successful input results in nothing (no familiar ok.). Erroneous input prints an extra blank line between the previous input and the next prompt." -- https://github.com/fuzzballcat/milliForthFitting a FORTH in 512 bytes https://niedzejkob.p4.team/bootstrap/ alternate link: https://compilercrim.es/bootstrap/miniforth/

"Fitting a FORTH in 512 bytes"

the website contains a detailed architectural walkthru

Bootstrapping a Forth in 40 lines of Lua code

https://users.ece.cmu.edu/~koopman/stack_computers/appb.html

https://github.com/larsbrinkhoff/lbForth

"Self-hosting metacompiled Forth, bootstrapping from a few lines of C; targets Linux, Windows, ARM, RISC-V, 68000, PDP-11, asm.js."

https://incoherency.co.uk/collapseos/primer.txt.html https://incoherency.co.uk/collapseos/dict.txt.html

See also https://incoherency.co.uk/collapseos/hal.txt.html

http://amforth.sourceforge.net/

http://www.openfirmware.info/Building_OFW_to_Run_Under_BIOS "Open Firmware provides a Forth environment and a lot of hooks into your system. The build instructions do not match the current directory layout, but you can figure it out." [2]

https://web.archive.org/web/20160405062053/http://eli.elilabs.com/~rj/dreams/ " Dreams is a message-passing Forth. " [3]

https://web.archive.org/web/20120414192318/http://home.arcor.de/a.s.kochenburger/minforth.html

See entry in plChMinLangs.txt

From Section 1.1. Gullwing Programmer Model Summary, pdf pages 4-5, of http://fpgacpu.ca/stack/ExtensionsToTheFlightProgrammingLanguage.pdf :

" 1.1.1 Data Stack The data stack is a 32-bit wide, 16-deep Last-In-First-Out buffer where most of the computations are performed. The instructions which operate up on it are:

LIT pushes a literal from the next memory location XOR replaces the two topmost elements with their bit-wise XOR AND replaces the two topmost elements with their bit-wise AND NOT replaces the topmost element with its binary complement 2* shifts the topmost element one bit to the right, shifting a zero into the least signi cant bit 2/ shift the topmost element one bit to the left, duplicating the sign bit + replaces the two topmost elements with their sum +* adds the second element to the first if the first element is an o dd numb er (multiply step) DUP pushes a copy of the topmost element DROP pops the topmost element OVER pushes a copy of the second element

1.1.2 Return Stack The return stack is a 32-bit wide, 16-deep Last-In-First-Out buffer where function call return addresses are kept. It is also used for sequential memory access and temporary storage. The instructions which operate up on it are:

CALL branches to an address stored in the next memory location and pushes the return address RET pops the return address and branches to it JMP jumps unconditionally to an address stored in the next memory location JMP0 pops the topmost element of the data stack, jumps to an address stored in the next memory location if it is equal to zero JMP+ pops the topmost element of the data stack, jumps to an address stored in the next memory location if it is p ositive R@+ pushes onto the data stack the content of an address on the top of the return stack, post-increments the address by one R!+ pops the topmost element on the data stack and stores it at the address on the top of the return stack, post-increments the address by one >R pops the topmost element on the data stack and pushes it onto the return stack R> pops the topmost element on the return stack and pushes it onto the data stack

1.1.3 Address Register The 32-bit wide address register is the main means of memory access. The instructions which operate up on it are: >A pops the topmost element of the data stack and stores it into the address register A> pushes a copy of the address register onto the data stack A@ fetches from the address in the address register and pushes the data onto the data stack A! pops the topmost element of the data stack and stores it at the address in the address register A@+ fetches from the address in the address register and pushes the data onto the data stack, post-increments the address by one A!+ pops the topmost element of the data stack and stores it at the address in the address register, post- increments the address by one

1.1.4 Other There are six instructions not tied to the Stacks or the address register: NOP Do es nothing but consume a pro cessor cycle. UNDEF[0-3] four op co des which are still unused and are currently defined as NOPs PC@ Fetches the next group of instructions into the Instruction Shift Register. There are six instruction slots or one literal p er memory word. This instruction is invisible to the programmer and compiled automatically by the ALIGN kernel function. "

See Appendix A in Second-Generation Stack Computer Architecture by Charles Eric LaForest

See also the Flight-related links at http://fpgacpu.ca/stack/index.html :

http://cowlark.com/2019-05-21-fforth/index.html

"fforth’s got two real claims to fame: the first is that it’s written in portable C without giving up too much performance, and the second is that it’s a single C source file which is also a runnable shell script containing an awk script and Forth source.

The reason for the latter is that running the source file as a shell script will pull Forth word definitions out of specially formatted comments in the source, recompile them using a simplified Forth compiler subset in awk, and patch the source with the updated compiled versions. This means that I can avoid the traditional Forth bootstrap phase of having to hand-compile enough of the interpreter to interpret the rest, making the whole system significantly easier to use and robust."

https://github.com/nineties/planckforth/blob/main/bootstrap.fs

"Bootstrapping a Forth interpreter from hand-written tiny ELF binary"

"Builtin Words

code name stack effect semantics Q quit ( n -- ) Exit the process C cell ( -- n ) The size of Cells h &here ( -- a-addr ) The address of 'here' cell l &latest ( -- a-addr ) The address of 'latest' cell k key ( -- c ) Read character t type ( c -- ) Print character j jump ( -- ) Unconditional branch J 0jump ( n -- ) Jump if a == 0 f find ( c -- xt ) Get execution token of c x execute ( xt -- ... ) Run the execution token @ fetch ( a-addr -- w ) Load value from addr ! store ( w a-addr -- ) Store value to addr ? cfetch ( c-addr -- c ) Load byte from addr with sign extension $ cstore ( c c-addr -- ) Store byte to addr d dfetch ( -- a-addr ) Get data stack pointer D dstore ( a-addr -- ) Set data stack pointer r rfetch ( -- a-addr ) Get return stack pointer R rstore ( a-addr -- ) Set return stack pointer i docol ( -- a-addr ) Get the code pointer of interpreter e exit ( -- ) Exit current function L lit ( -- n ) Load immediate S litstring ( -- c-addr ) Load string literal + add ( a b -- c ) c = (a + b)

| or ( a b -- c ) c = (a | b) |

( shl ( a b -- c ) c = a 1 b (logical) % sar ( a b -- c ) c = a >> b (arithmetic) v argv ( -- a-addr u ) argv and argc V version ( -- c-addr ) Runtime infomation string "

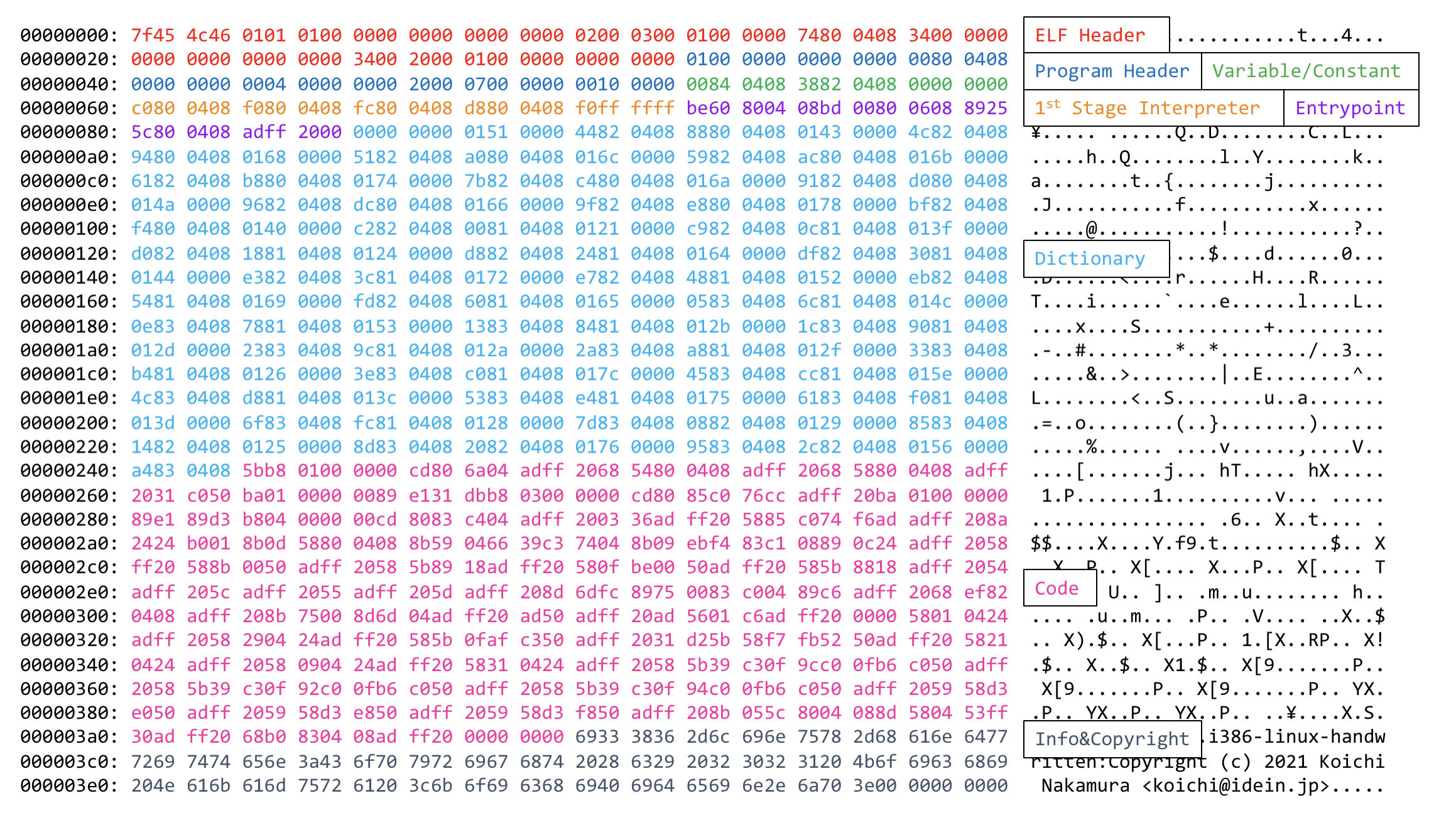

annotated hex dump of the hand-written ELF binary is at: https://github.com/nineties/planckforth/blob/main/planck.xxd

the commands that are fed to that binary to further bootstrap are at: https://github.com/nineties/planckforth/blob/main/bootstrap.fs

a pic of the binary layout is at:

https://github.com/Reschivon/movForth

" Words available during immediate mode:

+ - * / SWAP ROT DUP DROP . = SHOW ' , SEE [ ] IMMEDIATE ALLOT @ ! BRANCH BRANCHIF LITERAL HERE CREATE

Words available during runtime:

+ - * / BRANCH BRANCHIF . DUP DROP = LITERAL ! @ MALLOC "

targets WASM

https://el-tramo.be/blog/waforth/ https://el-tramo.be/waforth/

https://github.com/AZHenley/goforth

http://www.call-with-current-continuation.org/uf/uf.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/STOIC

http://www.complang.tuwien.ac.at/anton/euroforth/ef13/papers/ertl-paf.pdf

Portable Assembly Forth

"The main innovations of PAF are: tags indicate the control flow for indirect branches and calls; and PAF has two kinds of calls and definitions: the ABI ones follow the platform’s calling convention and are useful for interfacing to the outside world, while the PAF ones allow tail-call elimination and are useful for implementing general control structures" -- [5]

"...Forth is a good basis for a portable as- sembly language. However, there are features that are problematic in this context: In particular, in Forth the stack depth is not necessarily statically determined (unlike in the JVM), even though in nearly all Forth code the stack depth is actually statically determined (known to the programmer, but not always the Forth system). So we change these language features for PAF. A number of higher-level features of Forth are beyond the goal of a portable assembly language, so PAF does not support them. On the other hand, there are a few things that are missing in standard Forth that have to be added to PAF, such as words for accessing 16-bit quantities in memory " -- [6]

" PAF has restrictions and features that allow the compiler to statically determine the stack depth. As a consequence, in PAF there is no need to im- plement the stacks in memory, with a stack pointer for each stack (data stack and return stack for cells, floating-point stack for floating-point values). In contrast, Forth needs to have a separate mem- ory area and stack pointer for each stack, and while stack items can be kept in registers for most of the code, there are some words (in particular, execute) and code patterns (unbalanced stack effects on con- trol flow joins), that force stack items into memory and usually also force stack pointer updates. This property of Forth is avoided in PAF by requiring balanced stack effects on control flow joins (see Section 3.9), and by replacing execute with exec.tag (see Section 3.10); all definition ad- dresses returned for a particular tag are required to have compatible stack effects, so exec.tag has a statically determined stack effect " -- [7]

" PAF also supports indirect gotos: ’name /tag produces the address of label name, and goto/tag jumps to a label passed on the stack. The tag indi- cates which gotos can jump to which labels; a PAF program must not jump to a label address gener- ated with a different tag. E.g., a C compiler target- ing PAF could use a separate tag for each switch statement and the labels occuring there. These tags are useful for register allocation. One can use different tags when taking the address of the same label several times, and this may result in different label addresses, with the code at each tar- get address matched to the gotos that use that tag (i.e., several entry points for the same PAF label). Whichever method of control flow you use, on a control flow join the statically determined stack depth has to be the same on all joining control flows. This ensures that the PAF compiler can always de- termine the stack depth and can map stack items to registers even across control flow. This is a re- striction compared to Forth, but most Forth code conforms with this restriction. Breaking this rule is detected and reported as error by the PAF com- piler. So the tags have another benefit in connection with the stack-depth rule: The static stack depth for a given tag must be the same (for all labels and all gotos), but they can be different for different tags. If there were no tags, all labels and gotos in a definition would have to have the same stack depth " -- [8]

https://github.com/zeroflag/punyforth

http://www.ultratechnology.com/chips.htm

https://zserge.com/posts/too-many-forths/