![[Home]](http://www.bayleshanks.com/cartoonbayle.png)

In this part we'll focus on instruction sets, addressing modes, etc, rather than on other aspects of processors such as pipelining.

Close to machine language (bung a 20-bit address, but by using a 16-bit address and 4-bit index. This is the root of the 64k segment size problem that dogs DOS to this day.

Since DOS only ran in 8086 mode there was no easy way to address more than one meg of memory, and various standards were set up to allow access to addresses beyond the 1 meg barrier. The bug in the '286 was useful in that it allowed 8086 mode programs to see the first 64k above 1 meg. It involved some weird messing about with the keyboard controller to toggle the state of the 21st address line, and this is why you still see on some syt not exactly; most assembly languages allow the programmer to define alphanumeric labels for code positions and alphanumeric variable names) Linear imperative sequence of opcodes; statements, not expressions No assignment operator to assign to a variable; the 'alphanumeric variable names' mentioned above just map to a single memory location Registers or stack separate from memory Condition flags Untyped Goto and bne style control flow Addressing modes at least 3: immediate, register (or memory), indirect (tho see Parallax Propeller which uses self-modifying code in lieu of indirect) operations on fixed width data (e.g. "assume these memory locations contain 8-bit ints and add them" or "assume these memory locations contain 32-bit floats and add them") sometimes macros: for generating inline, as opposed to called, subroutines

For more inspiration about the sorts of instructions that might go into a VM, one might look at popular CPU instruction sets.

My purpose in including this section is NOT to teach the reader the basics of assembly language and computer architecture; i assume that the reader already knows that. I just want to give you more food for thought about 'minimal' programming languages.

Links:

the winner was: general purpose registers

From http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/teaching/0405/CompArch/mynotes.pdf :

Classic RISC Addressing Modes:

Less RISCy addr modes (ARM and PowerPC?):

CISC Addressing Modes:

Links:

regularity vs code density:

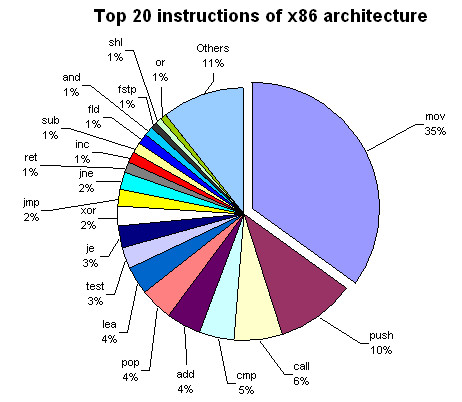

http://www.strchr.com/x86_machine_code_statistics

distribution by instruction length: 1 4.77% 2 17.67% 3 18.72% 4 12.28% 5 13.78% 6 15.60% 7 13.30% 8 2.46% 9 0.01% 10 1.02% 11 0.41%

top 20 instructions: mov 35% push 9.99941228328% call 6.01175433441% cmp 4.62415515721% add 4.31295915369% pop 4.08257419924% lea 3.85953570379% test 2.79400528945% je 2.74316779312% xor 2.44255069057% jmp 2.22421392889% jne 2.19541580958% ret 1.45224801646% inc 1.36320893329% sub 1.32677049662% fld 1.29180135175% and 1.10843373494% fstp 1.03967087864% shl 0.84748751102% or 0.738172200999% Others 10.5436379665%

number of operands: 0 3% 1 37% 2 60%

addressing modes: immediate 20% register 56% absolute address 1% indirect address 23%

instruction formats (note the destination comes first in the following): register-memory 35.4% register-register 26.5% register-immediate 16% memory-register 15.2% memory-immediate 6.8%

" The most popular instruction is MOV (35% of all instructions). Note that PUSH is twice more common than POP. These instructions are used in pairs for preserving EBP, ESI, EDI, and EDX registers across function calls, and PUSH is also used for passing arguments to functions; that's why it is more frequent. CALLs to functions are also very popular.

More than 50% of all code is dedicated to moving things between registers and memory (MOV), passing arguments, saving registers (PUSH, POP), and calling functions (CALL). Only 4th instruction (CMP) and the following ones (ADD, LEA, TEST, XOR) do actual calculations.

From conditional jumps, JE and JNE (equal and not equal) are the most popular. CMP and TEST are commonly used to check conditions. The percentage of the LEA instruction is surprisingly high, because MS VC++ compiler generates it for multiplications by constant (e.g., LEA eax, [eax*4+eax]) and for additions and subtractions when the result should be saved to another register, e.g.:

LEA eax, [ecx+04] LEA eax, [ecx+ecx]

The compiler also pads the code with harmless forms of LEA (for example, the padding may be LEA edi, [edi]). As is easy to see, the top 20 instructions include all logical operations (AND, XOR, OR) except NOT.

Though LAME encoder uses MMX technology instructions, their share in the whole code of the program is very low. Two FPU instructions (FLD and FSTP) appears in the top 20.

But what about other instructions? It turns out that multiplication and division are very rare: IMUL takes 0.13%, IDIV takes 0.04%, and both MUL and DIV do 0.02%. Even string operations such as REPZ SCASB or REPZ MOVSB are more common (0.32%) than all IMULs and IDIVs. On the contrary, FMUL is more common than FADD (0.71% versus 0.27%). "

Table 3:Most used x86 instructions...in DOS application

mov reg reg shl push add inc pop jz les shl 2 arg mov reg mem mov reg mem

Rank instruction # of MOP execution frequency 1 mov r16 r16 1 12.5% 2 shl r16 1 6.8% 3 push r16 2 5.1% 4 add r16 r16 1 5.1% 5 inc r16 1 4.1% 6 pop r16 2 4.0% 7 jz i8 1 3.6% 8 les r16 m16d8 4 3.3% 9 shl r16 i8 1 3.0% 10 mov r16 m16d0 1 2.9% 11 mov r16 m16d8 1 2.7% 12 jge i8 1 2.0% 13 wait 1 1.8% 14 cmp m16d16 i8 2 1.7% 15 jnz i8 1 1.6% 16 dec r16 1 1.5% 17 jmpn i8 1 1.5% 18 cmp m16d16 r16 2 1.5% 19 jl i8 1 1.3% 20 calln i16 ? 1.3% 21 mov r16 i16 1 1.2% 22 mov r8 r8 1 1.1% 23 mov r16 m16d16 1 1.1% 24 jle i8 1 1.0% 25 or r16 r16 1 1.0% 26 cmp r16 m16d8 2 1.0% 27 mov m16d0 r16 1 0.9% 28 mov r8 m8d0 1 0.9% 29 retn ? 0.8% 30 push m16d8 3 0.7% 31 cmp r16 m16d0 2 0.7% 32 jae i8 1 0.7% 33 cmp r16 i8 1 0.7% 34 stosb 2 0.6% 35 mov m16d8 r16 1 0.6% 36 scasb 3 0.6% 37 mov m16d16 r16 1 0.6% 38 movsw 4 0.6% 39 sub r16 r16 1 0.6% 40 movsb 4 0.6% 41 cmp m8d0 i8 2 0.5% 42 retf ? 0.5% 43 jb i8 1 0.5% 44 xchg r16 r16 1 0.4% 45 xor r16 r16 1 0.4% 46 add r16 i8 1 0.4% 47 clc 1 0.3% 48 cmp r8 m8d0 2 0.3% 49 jmpn i16 1 0.3% 50 jg i8 1 0.3% 51 cmp i16 r16 1 0.3% 52 stosw 2 0.3% 53 loop i8 2 0.3% 54 imul r16 r16 i16 1 0.3% 55 cmp m16d0 i8 2 0.3% 56 add r16 m16d8 2 0.3% 57 cmp r16 m16d16 2 0.3% 58 or r8 r8 1 0.3% 59 imul r16 r16 i8 1 0.3% 60 les r16 m16d0 4 0.3% 61 mov m8d0 r8 1 0.3% 62 fld m32d0 3 0.3% 63 xor r16 m16d16 2 0.2% 64 cmp r8 i8 1 0.2% 65 leave 3 0.2%

TOTAL 90.8%

Table 4: Most used x86 instructions...in Windows95 applications

push mov reg mem jz pop mov reg reg inc mov reg mem xor jnz calln

Rank instruction # of MOP execution frequency 1 push r32 2 8.4% 2 mov r32 m32d8 1 7.1% 3 jz i8 1 5.7% 4 pop r32 1 4.2% 5 mov r32 r32 1 4.0% 6 inc r32 1 3.0% 7 mov r32 m32d0 1 2.9% 8 xor r32 r32 1 2.7% 9 jnz i8 1 2.7% 10 calln i32 ? 2.2% 11 cmp r32 r32 1 2.2% 12 mov r16 m16d8 1 2.1% 13 test r32 r32 1 2.1% 14 retn i32 ? 1.9% 15 jl i8 1 1.9% 16 mov r8 m8d8 1 1.7% 17 cmp r32 i32 1 1.6% 18 add r32 r32 1 1.5% 19 add r32 i8 1 1.3% 20 cmp m32d32 i8 2 1.3% 21 jz i32 1 1.3% 22 lea r32 m32d0 1 1.3% 23 lea r32 m32d8 1 1.3% 24 cdq 1 1.3% 25 mov m32d8 r32 1 1.3% 26 cmp r8 i8 1 1.2% 27 sub r32 r32 1 1.2% 28 cmp m32d8 i8 2 1.1% 29 jmpn i8 1 1.1% 30 sub r32 m32d8 1 1.1% 31 and r32 i8 1 1.0% 32 test r8 i8 1 0.9% 33 jnz i32 1 0.9% 34 mov r16 m16d0 1 0.8% 35 mov r8 m8d0 1 0.8% 36 mov m16d8 r16 1 0.7% 37 cmp m32d0 i8 2 0.7% 38 mov m32d0 r32 1 0.7% 39 jae i8 1 0.7% 40 mov r32 m32d32 1 0.6% 41 movzx r32 r32 1 0.6% 42 call m32d0 ? 0.6% 43 sub r32 i8 1 0.5% 44 mov r32 i32 1 0.5% 45 shr r32 i8 1 0.5% 46 movsw 4 0.5% 47 jle i8 1 0.5% 48 imul r32 r32 i32 1 0.5% 49 movsb 4 0.4% 50 jg i8 1 0.4% 51 and r8 i8 1 0.4% 52 and r16 i16 1 0.4% 53 push m32d8 3 0.4% 54 cmp r16 i16 1 0.4% 55 sub r32 i32 1 0.4% 56 movzx r8 m8d0 1 0.4% 57 mov m8d0 r8 1 0.3% 58 dec r32 1 0.3% 59 test r8 r8 1 0.3% 60 jmpn i32 1 0.3% 61 retn ? 0.3% 62 call r32 ? 0.3% 63 cmp m32d0 r32 2 0.3% 64 push i8 2 0.3% 65 cmp m16d8 r16 2 0.3%

TOTAL 90.5%

Table 5: Micro-operation frequencies

Rank Micro-operation Frequency 1 ld 19.7% 2 mov 9.6% 3 st 9.5% 4 subin 5.5% 5 movm (masked mov) 4.7% 6 shl 4.5% 7 asidn 4.1% 8 cmp 3.6% 9 addin 3.5% 10 add 3.4% 11 inc 2.9% 12 cmpi 2.7% 13 jiz 2.5% 14 wrseg 2.3% 15 ji 2.1% 16 shli 1.8% 17 movi 1.3% 18 jinl 1.2% 19 dec 1.2%

ld mov st subin movm (masked mov) shl asidn cmp addin add inc cmpi jiz 20 jinz 1.1%

(bayle: i have no idea what movm and asidn do; see below for some of the others)

" The micro operations are based on the superscalar model Table 5 lists the most used micro operations. The most significant micro operations are ld (load from memory), st (store to memory) and mov (register-to- register data movement).

...

Optimization for frequently executed instructions: PUSH and POP "

The subin MOP subtracts the register sp with an immediate value (2) and stores the result back to the register sp "

PUSH = subin; st POP = ld; addin

" SHL is simply shift left. SHL is cool because it's a quick way to multiply (amongst other things) a value by 2,4,8, etc because every time you SHL you double the value. "

" measurements on the VAX show that these addressing modes (immediate, direct, register indirect, and base+displacement) represent 88% of all addressing mode usage. • similar measurements show that 16 bits is enough for the immediate 75 to 80% of the time • and that 16 bits is enough of a displacement 99% of the time. " -- http://www.sdsc.edu/~allans/cs141/L2.ISA.pdf

Table 6.1. Dynamic Instruction Execution Frequencies for important Forth primitives.

NAMES FRAC LIFE MATH COMPILE AVE CALL 11.16% 12.73% 12.59% 12.36% 12.21% EXIT 11.07% 12.72% 12.55% 10.60% 11.74% VARIABLE 7.63% 10.30% 2.26% 1.65% 5.46% @ 7.49% 2.05% 0.96% 11.09% 5.40% 0BRANCH 3.39% 6.38% 3.23% 6.11% 4.78% LIT 3.94% 5.22% 4.92% 4.09% 4.54% + 3.41% 10.45% 0.60% 2.26% 4.18% SWAP 4.43% 2.99% 7.00% 1.17% 3.90% R> 2.05% 0.00% 11.28% 2.23% 3.89% >R 2.05% 0.00% 11.28% 2.16% 3.87% CONSTANT 3.92% 3.50% 2.78% 4.50% 3.68% DUP 4.08% 0.45% 1.88% 5.78% 3.05% ROT 4.05% 0.00% 4.61% 0.48% 2.29% USER 0.07% 0.00% 0.06% 8.59% 2.18% C@ 0.00% 7.52% 0.01% 0.36% 1.97% I 0.58% 6.66% 0.01% 0.23% 1.87%

AND 0.17% 3.12% 3.14% 0.04% 1.61% BRANCH 1.61% 1.57% 0.72% 2.26% 1.54% EXECUTE 0.14% 0.00% 0.02% 2.45% 0.65%

Instructions: 2051600 1296143 6133519 447050

Table 6.2. Static Instruction Execution Frequencies for important Forth primitives.

6.3.2 Static instruction frequencies

NAMES FRAC LIFE MATH COMPILE AVE CALL 16.82% 31.44% 37.61% 17.62% 25.87% LIT 11.35% 7.22% 11.02% 8.03% 9.41% EXIT 5.75% 7.22% 9.90% 7.00% 7.47% @ 10.81% 1.27% 1.40% 8.88% 5.59% DUP 4.38% 1.70% 2.84% 4.18% 3.28% 0BRANCH 3.01% 2.55% 3.67% 3.16% 3.10% PICK 6.29% 0.00% 1.04% 4.53% 2.97% + 3.28% 2.97% 0.76% 4.61% 2.90% SWAP 1.78% 5.10% 1.19% 3.16% 2.81% OVER 2.05% 5.10% 0.76% 2.05% 2.49% ! 3.28% 2.12% 0.90% 2.99% 2.32% I 1.37% 5.10% 0.11% 1.62% 2.05% DROP 2.60% 0.85% 1.69% 2.31% 1.86% BRANCH 1.92% 0.85% 2.09% 2.05% 1.73% >R 0.55% 0.00% 4.11% 0.77% 1.36% R> 0.55% 0.00% 4.68% 0.77% 1.50% C@ 0.00% 3.40% 0.61% 0.34% 1.09%

Instructions: 731 471 2777 1171

Table 6.3. Dynamic Instruction Execution Frequencies for RTX 32P Instruction types.

FRAC LIFE MATH AVEOP 57.54% 46.07% 49.66% 51% CALL 19.01% 26.44% 19.96% 22% EXIT 10.80% 12.53% 16.25% 13% OP+CALL 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0% OP+EXIT 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0% CALL+EXIT 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0% OP+CALL+EXIT 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0% COND 5.89% 9.95% 6.56% 7% LIT 6.76% 5.01% 7.57% 6% LIT-OP 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0% VARIABLE-OP 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0% VARIABLE-OP-OP 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0%

Instructions: 8381513 1262079 940448

OP-OP 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0%

local-variable loads: 34.5% local-variable stores: 7% loads from memory: 20.2% stores to memory: 4% compute (integer/floating point): 9.2% branches: 7.9% calls/returns: 7.3% push constant: 6.8% misc stack ops: 2.1% new objects: 0.4% all others: 0.6%

memory reference: 34% (LOAD (load and push to top of stack) 18%, STOR (store from top of stack) 7%, LDX (load into index register) 3%) immediate: 17% branches: 16% stack ops: 16% privileged memory reference: 5% field & bit: 5% linkage & control: 5% shifts: 1%

Table 3. Distribution of memory references (note: by addressing mode) address type nominal use of address mode percent of LOADs, percent of STORs DB+ global scalar 7 7 DB+, I, X global array 3 10 Q- LOAD: value parameter 20 Q- STOR: return value 17 Q-, I reference parameter scalar 4 5 Q-, I, X array parameter 5 6 Q+ local scalar 27 44 Q+, I, X local array 7 4 S- temporary 2 1 P+- constant 12 not allowed direct array (no indirection) 13 6

note: the DB register points to globals; X is the index register; the Q register points to locals; S points to the stack; P is the program counter; I presumably means indirection/dereferencing.

branches: 68% conditional upon status flags 19% unconditional 13% conditional upon the first bit on top of the stack

81% of conditional branches and 86% of unconditional were direct P-relative; the rest are indirect (the operand specifies a location L which itself contains a 16-bit displacement from L; L plus the displacement is the branch target)

branch distances (of direct branches only): distance % of direct BR % of direct BCC 128-225 5 64-127 3 32-63 3 16-31 42 20 8-15 10 30 4-7 12 26 2-3 15 23 1 9

"

Stackops. The stack operators are those whose operands are implicitly at the top of the stack. Their operation was demonstrated by Ackermann's function. One result of the measurement was that 5 percent of all instructions executed were paired stackops. Paired stackops reduce memory traffic to the CPU and improve the code com- pression otherwise inherent in the stack architecture. Of the most common stackops, only one is an arithmetic operator as shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Dominant stackops.

DUP 3% Duplicate top of stack STAX 3% Store top of stack in index reg and delete ZERO 2% Push a zero onto the top of stack CMP 1% Compare top two words, set conditon code XCH 1% Exchange top two words DECA 1% Subtract one from the top of stack

Again, percentages are expressed as a fraction of all instructions executed. Much of the use of DUP could probably be eliminated by including a nondestructive STOR instruction, which does not pop the stack, but merely copies it to the specified DB-, Q-, or S-relative location. "

" Immediates. One quarter of the immediate group were executions of LDXI (load X immediate).

...

Table 6. Dominant immediates (aside from LDXI).

CMPI 3% Compare immediate value with TOS ADDI 2% Add immediate value to the TOS LDI 2% Load immediate value to the TOS SED 2% Enable, disable external interrupts ANDI 1% And immediate with the TOS

Table 7. Ten most frequent instructions in a multiprogramming benchmark.

LOAD 18% Load word onto the top of stack BCC 10% Branch on status condition STOR 7% Store word off the top of stack LDXI 4% Load immediate value into index register DUP 3% Duplicate the top of stack STAX 3% Store top of stack into index register BR 3% Unconditional branch CMPI 3% Compare immediate value with top of stack LDX 3% Load index register from memory EXF 3% Extract bit field from the top of stack

addressing mode usage (3 programs avg, 17% to 43%):

Register deferred (indirect): 13% avg, 3% to 24%) scaled 7% avg, 0% to 16% memory 3% avg, 1% to 6% misc 2% avg, 0% to 3%

"data addressing modes that are important: displacement, immediate, register indirect. Displacement size should be 12 to 16 bits. Immediate size should be 8 to 16 bits"

"

Typical Operations

Data Movement load/store (from/to memory) memory-to-memory move register-to-register move input/output (from/to I/O device) push/pop (to/from stack)

Arithmetic integer (binary + decimal) or FP add, subtract, multiply, divide

Logical not, and, or, set, clear

Shift shift left/right, rotate left/right

Control (Jump/Branch) unconditional, conditional

Subroutine Linkage call, return

Interrupt trap, return

Synchronization test&set (atomic read-modify-write)

String search, translate "

"

Addressing Modes Addressing mode Example Meaning Register Add R4,R3 R4 R4+R3 Immediate Add R4,#3 R4 R4+3 Displacement Add R4,100(R1) R4 R4+Mem[100+R1] Register indirect Add R4,(R1) R4 R4+Mem[R1] Indexed Add R3,(R1+R2) R3 R3+Mem[R1+R2] Direct or absolute Add R1,(1001) R1 R1+Mem[1001] Memory indirect Add R1,@(R3) R1 R1+Mem[Mem[R3]] Auto-increment Add R1,(R2)+ R1 R1+Mem[R2]; R2 R2+d Auto-decrement Add R1,-(R2) R2 R2-d; R1 R1+Mem[R2] Scaled Add R1,100(R2)[R3] R1 R1+Mem[100+R2+R3*d]

"

www.ece.iupui.edu/~johnlee/ECE565/lecture/ECE565.Ch2-ISA.pdf:

"

Top ten 80x86 instructions Rank Instruction % total execution 1 load 22% 2 conditional branch 20% 3 compare 16% 4 store 12% 5 add 8% 6 and 6% 7 sub 5% 8 move reg-reg 4% 9 call 1% 10 return 1%

Total 96%

From five SPECint92 program "

http://cmsc411.com/topics/instruction-set-architectures-action

" Support these simple instructions, since they will dominate the number of instructions executed: load, store, add, subtract, move register-register, and shift Compare equal, compare not equal, compare less, branch (with a PC-relative address at least 8 bits long), jump, call, and return "

" Use fixed instruction encoding if interested in performance, and use variable instruction encoding if interested in code size "

" Operand Size Usage

Frequency of reference by size

0% Doubleword (64-bit): integer: 0% floating point: 69%

Word: integer: 74% floating point: 31%

Halfword: integer: 19% floating point: 0%

Byte: integer: 7% floating point: 0%

Support these data sizes and types: 8-bit, 16-bit, 32-bit integers and 32-bit and 64-bit IEEE 754 floating point numbers

" -- http://www.ece.northwestern.edu/~kcoloma/ece361/lectures/Lec04-mips.pdf

A Few of the Most Frequent Instructions Complier % Sum VlsiCheck? % Sum Jump If !=0 10.30 10.3 Load Local Double-Word 7.04 7.04 Load LO 8.96 19.26 Load LO 6.39 13.43 Read Field 7.50 26.76 Store Local Double-Word 5.15 18.58 Load Immed 16-bit 5.51 32.27 Recover Stack Item 4.93 23.51 Add 4.94 37.21 Load Immed 8-bit 4.60 28.11 Read Indirect 4.6 41.81 Load Immed. 0 3.92 32.03 Recover Stack Item3.51 45.32 Read Indirect 3.11 35.14 Index Off Pointer Load GO 2.99 48.31 Jump If !=O 3.03 38.17

for two programs, a compiler (complier in chart; sic) and VlsiCheck?

" Statistics For "Standard" Partition Compiler VlsiCheck? Group % Sum Group % Sum LdlStore? 32.97 32.97 LdlStore? 35.15 35.15 RIW 19.59 52.57 RIW 14.14 49.29 CondJumps? 16.82 69.39 Stack Ops 12.23 61.52 Ld Immed 11.43 80.82 ALU Ops 10.76 72.28 ALU Ops 8.14 88.96 Ld Immed 10.53 82.81 Stack Ops 3.87 92.84 CondJumps? 8.42 91.23 Xfers 3.55 96.39 Xfers 5.31 96.54 Jumps 2.25 98.64 Jumps 1.75 98.29 Mise 1.35 99.99 Mise 1.67 99.96 Processes 0.01 100.0 Processes 0.04 100.0

Branches, Xfers, and Jumps Compiler VlsiCheck? Group % Sum Group % Sum CondJumps? 16.82 16.82 CondJumfs? 8.42 8.42 Xfers 3.55 20.37 Xfers 5.3 13.73 Jumps 2.25 22.62 Jumps 1.75 15.48

The tables ·and figures below show the most frequently executed instructions within each group of the Standard Partition. For the sake of brevity, only the first three or four instructions in each group are shown. Note that within each group only a few instructions account for most of the activity in that group, and that bounds and NIL checking (in Stack Ops group) cost only 5.14% of all instructions, even in a program like VlsiCheck?, that extensively reads and writes memory.

Opcode mnemonics are provided in the appendix.

Compiler VlsiCheck? Instr Group Over all Sum Instr Group Over all Sum

LdlStore?=32.97% Over All LdlStore?=35.15% Over All LLO 27.16 8.96 8.96 LLDB 20.04 7.04 7.04 LGO 9.06 2.99 11.95 LLO 18.17 6.39 13.43 LL1 7.29 2.40 14.35 SLDB 14.65 5.15 18.58 LL2 5.02 1.76 20.34

R/W=19.59% Over All R/W=14.14% Over All RF 38.23 7.49 7.49 RILP 21.96 3.11 3.11 RO 23.68 4.64 12.13 RO 13.00 1.84 4.95 RXLP 6.86 1.34 13.47 RDBL 10.38 1.47 6.42 RSTR 9.66 1.37 7.79

CondJumps?= 16.82% Over All Stack Ops = 12.23% Over All JZNEB 61.18 JZNEB 61.57 10.29 10.29 PUSH 40.30 4.93 4.93 JZEQB 7.87 1.32 11.61 NILCKL 21.78 2.66 7.59 JEQB 5.71 .96 12.57 BNDCK 10.37 1.33 8.92 NILCK 9.42 1.15 10.07

Ld Immed = 11.43% Over All ALU Ops=10.76% Over All LIW 47.31 5.41 5.41 MUL 24.16 2.60 2.60 LIB 13.95 1.59 7.00 ADD 21.62 2.33 4.93 LIO 13.49 1.54 8.54 SUB 12.98 1.40 6.33 LIl 9.79 1.12 9.66 INC 11.33 1.22 7.55

"

Appendix: Instruction Descriptions LLi, LGi, SLi, SGi Load or Store from the Local or Global Frame the i th variable LLB, LLDB, SLB, SLOB RF Ri Load or Store from the Local or Global Frame given a byte offset "0" indicates a double- word quantity Read a bit field from a 16-bit value Read the i th word from the pointer on the top of the stack RXLP,RILP Read a value, indexed or indirect with post indexing JZNEB, JZEQB, JEQB Conditional branches with a byte offset for the PC LIW, LIB, Li Load immediate values (word, byte, small constant) RECOVER Recover the previous top of stack by incrementing the stack pointer without modifying the contents of the stack MUL, ADD, SUB, INC Arithmetic operations BNDCK, NILCK, NILCKL Boundary and pointer check instructions

"

"

Statistics For "Memory Components" Partition Compiler VlsiCheck? Group % Sum Group % Sum Mem1 19.18 19.16 Meml 10.94 10.94 Mem2 16.78 35.94 Mem2 24.81 35.75

Statistics For "Instruction Length" Partition Compiler VlsiCheck? Group % Sum Group % Sum Length1 55.22 55.22 Length1 56.72 56.72 Length2 38.64 93.86 Length2 41.66 98.38 Length3 6.14 100.0 Length3 1.62 100.0 Average Length 1.51 1.45

"

there's more data in that paper that i didn't bother to copy to here

" Statistics about Control Flow Change

"

" Performance effect of various levels of optimization measurements from Chow[1983] for 12 small FORTRAN and PASCAL programs

Optimizations performed Percent faster Procedure integration only 10% Local optimizations only 5% Local optimizations + register allocations 26% Global and local optimizations 14% Local and global optimizations + register allocation 63% Local and global optimizations + procedure integration + register allocation 81%

"

Addressing mode usage frequencies:

tex:

displacement: 32 immediate: 43 register deferred: 24 scaled: 16 memory indirect: 1

spice:

displacement: 55 immediate: 17 register deferred: 3 scaled: 16 memory indirect: 6

gcc:

displacement: 40 immediate: 39 register deferred: 11 scaled: 5 memory indirect: 1

immediate size: 50% to 60% fit within 8 bits, 75% to 80% fit within 16 bits

" Linux C library on x86:

Instruction usage breakdown (by popularity): 42.4% mov instructions 5.0% lea instructions 4.9% cmp instructions 4.7% call instructions 4.5% je instructions 4.4% add instructions 4.3% test instructions 4.3% nop instructions 3.7% jmp instructions 2.9% jne instructions 2.9% pop instructions 2.6% sub instructions 2.2% push instructions 1.4% movzx instructions 1.3% ret instructions ...

This makes a little more sense broken into categories:

Load and store: about 50% total 42.4% mov instructions 2.9% pop instructions 2.2% push instructions 1.4% movzx instructions 0.3% xchg instructions 0.2% movsx instructions

Branch: about 25% total 4.9% cmp instructions 4.7% call instructions 4.5% je instructions 4.3% test instructions 3.7% jmp instructions 2.9% jne instructions 1.3% ret instructions 0.4% jle instructions 0.4% ja instructions 0.4% jae instructions 0.3% jbe instructions 0.3% js instructions

Arithmetic: about 15% total 5.0% lea instructions (uses address calculation arithmetic) 4.4% add instructions 2.6% sub instructions 1.0% and instructions 0.5% or instructions 0.3% shl instructions 0.3% shr instructions 0.2% sar instructions 0.1% imul instructions

So for this piece of code, the most numerically common instructions on x86 are actually just memory loads and stores (mov, push, or pop), followed by branches, and finally arithmetic--this low arithmetic density was a surprise to me! You can get a little more detail by looking at what stuff occurs in each instruction:

Registers used: 30.9% "eax" lines (eax is the return result register, and general scratch) 5.7% "ebx" lines (this register is only used for accessing globals inside DLL code) 10.3% "ecx" lines 15.5% "edx" lines 11.7% "esp" lines (note that "push" and "pop" implicitly change esp, so this should be about 5% higher) 25.9% "ebp" lines (the bread-and-butter stack access base register) 12.0% "esi" lines 8.6% "edi" lines

x86 does a good job of optimizing access to the eax register--many instructions have special shorter eax-only versions. But it should clearly be doing the same thing for ebp, and it doesn't have any special instructions for ebp-relative access.

Features used: 66.0% "0x" lines (immediate-mode constants) 69.6% "," lines (two-operand instructions) 36.7% "+" lines (address calculated as sum) 1.2% "*" lines (address calculated with scaled displacement) 48.1% "\[" lines (explicit memory accesses) 2.8% "BYTE PTR" lines (char-sized memory access) 0.4% "WORD PTR" lines (short-sized memory access) 40.7% "DWORD PTR" lines (int or float-sized memory) 0.1% "QWORD PTR" lines (double-sized memory)

So the "typical" x86 instruction would be an int-sized load or store between a register, often eax, and a memory location, often something on the stack referenced by ebp with an immediate-mode offset. Something like 50% of instructions are indeed of this form! "

A teaching language used on the web page http://www.plantation-productions.com/Webster/www.artofasm.com/Linux/HTML/ISA.html

" For example, most processors you find will have instructions like the following:

Data movement instructions (e.g., MOV)

Arithmetic and logical instructions (e.g., ADD, SUB, AND, OR, NOT)

Comparison instructions

A set of conditional jump instructions (generally used after the compare instructions)

Input/Output instructions

Other miscellaneous instructions "

" The Y86 CPU provides 20 instructions. Seven of these instructions have two operands, eight of these instructions have a single operand, and five instructions have no operands at all. The instructions are MOV (two forms), ADD, SUB, CMP, AND, OR, NOT, JE, JNE, JB, JBE, JA, JAE, JMP, BRK, IRET, HALT, GET, and PUT. "

HALT is program termination. BRK is a temporary halt that can be resumed from. JB and JB are JLT and JGT. IRET is return from interrupt. GET and PUT are input and output.

"The Y86 processor supports the register addressing mode7, the immediate addressing mode, the indirect addressing mode, the indexed addressing mode, and the direct addressing mode."

Later, they mention expansion to the NEG (arithmetic negation) instruction, and the SHL, SHR, ROL, ROR, and XOR instructions.

Links:

" At its inception, the programmer's view of the PDP-8 had only eight instructions and two registers (a 12-bit accumulator, AC, and a carry bit called the "link register", L). "

"PDP-8 •Very simple machine and instruction set •Has one register (the Accumulator) •12-bit instructions operate on 12-bit words •Very efficient implementation –35 operations along with indirect addressing, displacement addressing and indexing in 12 bits •The lack of registers is handled by using part of the first physical page of memory as a register file

PDP-8 Memory References •Main memory consisted of 4096 words divided into 32 128-word pages •Instructions with a memory reference had a 7-bit address plus two modifier bits (leaving 3 bits for opcode!) —Z/C bit Page 0 or current page (with this instruction) —D/I bit Direct or Indirect addressing •In addition the first 8 words of page 0 are treated as autoindex “registers” •Note that memory-indirect addressing was used because processor had no index registers Instruction Formats •A 3-bit opcode and three types of instructions —For opcodes 0–5 (6 basic instructions) we have single address mem ref with Z/C I/D bits •Opcode 6 is I/O with 6 device-select bits and 3 operation bits •Opcode 7 defines a register reference or microinstruction —Three groups, where bits are used to specify operation (e.g., clear accumulator) —Forerunner of modern microprogramming " -- http://umcs.maine.edu/~cmeadow/courses/cos335/COA11.pdf

" Basic instructions

000 – AND – AND the memory operand with AC.

001 – TAD – Two's complement ADd the memory operand to <L,AC> (a 12 bit signed value (AC) w. carry in L).

010 – ISZ – Increment the memory operand and Skip next instruction if result is Zero.

011 – DCA – Deposit AC into the memory operand and Clear AC.

100 – JMS – JuMp to Subroutine (storing return address in first word of subroutine!).

101 – JMP – JuMP.

110 – IOT – Input/Output Transfer (see below).

111 – OPR – microcoded OPeRations (see below).IOT (Input-Output Transfer) instructions

The PDP-8 processor defined few of the IOT instructions, but simply provided a framework. Most IOT instructions were defined by the individual I/O devices. 0 2 3 8 9 11 6=IOT Device Function

Device

Bits 3 through 8 of an IOT instruction selected an I/O device. Some of these device addresses were standardized by convention:

00 was handled by the processor and not sent to any I/O device (see below)

01 was usually the high-speed paper tape reader

02 was the high-speed paper tape punch

03 was the console keyboard (and any associated low-speed paper tape reader)

04 was the console printer (and any associated low-speed paper tape punch)Instructions for device 0 affected the processor as a whole. For example, ION (6001) enabled interrupt processing, and IOFF (6002) disabled it.

Function

Bits 9 through 11 of an IOT instruction selected the function(s) the device would perform. Simple devices (such as the paper tape reader and punch and the console keyboard and printer) would use the bits in standard ways:

Bit 11 caused the processor to skip the next instruction if the I/O device was ready

Bit 10 cleared AC

Bit 9 moved a word between AC and the device, initiated another I/O transfer, and cleared the device's "ready" flagThese operations took place in a well-defined order that gave useful results if more than one bit was set.

More complicated devices, such as disk drives, used these 3 bits in device-specific fashions. Typically, a device decoded the 3 bits to give 8 possible function codes. "

" OPR (OPeRate?)

Many operations were achieved using OPR, including most of the conditionals. OPR does not address a memory location; conditional execution is achieved by conditionally skipping one instruction, which was typically a JMP.

The OPR instruction was said to be "microcoded." This did not mean what the word means today (that a lower-level program fetched and interpreted the OPR instruction), but meant that each bit of the instruction word specified a certain action, and the programmer could achieve several actions in a single instruction cycle by setting multiple bits. In use, a programmer would write several instruction mnemonics alongside one another, and the assembler would combine them with OR to devise the actual instruction word. Many I/O devices supported "microcoded" IOT instructions.

Microcoded actions took place in a well-defined sequence designed to maximize the utility of many combinations.

The OPR instructions came in Groups. Bits 3, 8 and 11 identify the Group of an OPR instruction, so it was impossible to combine the microcoded actions from different groups. Group 1

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11

___________________________________

| 1| 1| 1| 0| | | | | | | | |

|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|

|CLA CMA RAR BSW

CLL CML RAL IAC

Execution order 1 1 2 2 4 4 4 3 7200 – CLA – Clear Accumulator

7100 – CLL – Clear the L Bit

7040 – CMA – Ones Complement Accumulator

7020 – CML – Complement L Bit

7001 – IAC – Increment <L,AC>

7010 – RAR – Rotate <L,AC> Right

7004 – RAL – Rotate <L,AC> Left

7012 – RTR – Rotate <L,AC> Right Twice

7006 – RTL – Rotate <L,AC> Left Twice

7002 – BSW – Byte Swap 6-bit "bytes" (PDP 8/e and up)In most cases, the operations are sequenced so that they can be combined in the most useful ways. For example, combining CLA (CLear Accumulator), CLL (CLear Link), and IAC (Increment ACcumulator) first clears the AC and Link, then increments the accumulator, leaving it set to 1. Adding RAL to the mix (so CLA CLL IAC RAL) causes the accumulator to be cleared, incremented, then rotated left, leaving it set to 2. In this way, small integer constants were placed in the accumulator with a single instruction.

The combination CMA IAC, which the assembler let you abbreviate as CIA, produced the arithmetic inverse of AC: the twos-complement negation. Since there was no subtraction instruction, only the twos-complement add (TAD), computing the difference of two operands required first negating the subtrahend.

A Group 1 OPR instruction that has none of the microprogrammed bits set performs no action. The programmer can write NOP (No Operation) to assemble such an instruction. Group 2, Or Group

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11

___________________________________

| 1| 1| 1| 1| | | | | 0| | | 0|

|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|

|CLA SZA OSR

SMA SNL HLT

2 1 1 1 3 3 7600 – CLA – Clear AC

7500 – SMA – Skip on AC < 0 (or group)

7440 – SZA – Skip on AC = 0 (or group)

7420 – SNL – Skip on L ≠ 0 (or group)

7404 – OSR – logically 'or' front-panel switches with AC

7402 – HLT – HaltWhen bit 8 is clear, a skip is performed if any of the specified conditions are true. For example "SMA SZA", opcode 7540, skips if AC ≤ 0.

A Group 2 OPR instruction that has none of the microprogrammed bits set is another No-Op instruction. Group 2, And Group

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11

___________________________________

| 1| 1| 1| 1| | | | | 1| | | 0|

|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|

|CLA SNA OSR

SPA SZL HLT

2 1 1 1 3 2 7410 – SKP – Skip Unconditionally

7610 – CLA – Clear AC

7510 – SPA – Skip on AC ≥ 0 (and group)

7450 – SNA – Skip on AC ≠ 0 (and group)

7430 – SZL – Skip on L = 0 (and group) When bit 8 is set, the Group 2, Or skip condition is inverted: the skip is not performed if any of the group 2, Or conditions are true, meaning that all of the specified skip conditions must be true. For example, "SPA SNA", opcode 7550, skips if AC > 0. If none of bits 5–7 are set, then the skip is unconditional. Group 3

Unused bit combinations of OPR were defined as a third Group of microprogrammed actions mostly affecting the MQ (Multiplier/Quotient) register.

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11

___________________________________

| 1| 1| 1| 1| | | | | | | | 1|

|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|__|

|CLA SCA \_ _/

| MQA MQL CODE

1* 2 2 2 3 7601 – CLA – Clear AC

7501 – MQA – Multiplier Quotient with AC (logical or MQ into AC)

7441 – SCA – Step counter load into AC

7421 – MQL – Multiplier Quotient Load (Transfer AC to MQ, clear AC)

7621 – CAM – CLA + MQL clears both AC and MQ.Typically CLA and MQA were combined to transfer MQ into AC. Another useful combination is MQA and MQL, to exchange the two registers.

Three bits specified a multiply/divide instruction to perform:

7401 – No operation

7403 – SCL – Step Counter Load (immediate word follows, PDP-8/I and up)

7405 – MUY – Multiply

7407 – DVI – Divide

7411 – NMI – Normalize

7413 – SHL – Shift left (immediate word follows)

7415 – ASR – Arithmetic shift right

7417 – LSR – Logical shift right"

See also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PDP-8#Examples

" The CPU contained eight general-purpose 16-bit registers (R0 to R7). Register R7 was the program counter (PC). Although any register could be used as a stack pointer, R6 was the stack pointer (SP) used for hardware interrupts and traps. "

Addressing modes: register, register indirect, register indirect postincrement, register double indirect postincrement, register indirect predecrement, register double indirect predecrement, (register + offset) indirect, , (register + offset) double indirect

" Double-operand instructions "

General: MOV Logic: CMP, XOR Bit: BIT (bit test), BIC (bit clean), BIS (bit set), Arithmetic: ADD, SUB, MUL, DIV Bit arithmetic: ASH (Arithmetic shift), ASHC (Arithmetic shift combined: (R,R+1) 1= 1 1062 ASRB 0063 ASL Shift left: dest <<= 1 1063 ASLB 0064 MARK Return from subroutine, skip 0..63 instruction words 1064 MTPS Move to status: PS = src 0065 MFPI Move from previous I space: −(SP) = src 1065 MFPD Move from previous D space: −(SP) = src 0066 MTPI Move to previous I space: dest = (SP)+ 1066 MTPD Move to previous D space: dest = (SP)+ 0067 SXT Sign extend: dest = (16 copies of N flag) 1067 MFPS Move from status: dest = PS

"

" Conditional branch instructions

...

Opcode Mnemonic Effect 0000xx (System instructions) 0004xx BR Branch unconditionally 0010xx BNE Branch if not equal (Z=0) 0014xx BEQ Branch if equal (Z=1) 0020xx BGE Branch if greater that or equal (N

| V = 0) |

| V = 1) |

| Z = 0) |

| Z = 1) |

" Jump and subroutine instructions

JMP (jump)

JSR (jump to subroutine--see below)

RTS (return from subroutine--see below)

MARK (support of stack clean-up at return)

EMT (emulator trap)

TRAP, BPT (breakpoint trap)

IOT (input/output trap)

RTI & RTT (return from interrupt)The JSR instruction could save any register on the stack. Programs that did not need this feature specified PC as the register (JSR PC,address) and the routine returned using RTS PC. If a routine were called with, for instance, "JSR R4, address", then the old value of R4 would be on the top of the stack and the return address (just after JSR) would be in R4. This let the routine gain access to values coded in-line by specifying (R4)+, or to in-line pointers by specifying @(R4)+. The autoincrementation moved past these data, to the point at which the caller's code resumed. Such a routine would have to specify RTS R4 to return to its caller. "

" Miscellaneous instructions

HALT, WAIT (wait for interrupt)

RESET (reset UNIBUS)Condition-code operations

CLC, CLV, CLZ, CLN, CCC (clear relevant condition code)

SEC, SEV, SEZ, SEN, SCC (set relevant condition code)The four condition codes in the processor status word (PSW) are

N indicating a negative value

Z indicating a zero (equal) condition

V indicating an overflow condition, and

C indicating a carry condition.SCC and CCC respectively set and clear all four condition codes. "

Both https://www.semipublic.comp-arch.net/wiki/RISC_versus_CISC and http://www.cpushack.com/CPU/cpu4.html call the Motorola 68000 'elegant' so maybe we should take a look at it.

My purpose in including this section is NOT to teach the reader the basics of assembly language and computer architecture; i assume that the reader already knows that. I just want to give you more food for thought about 'minimal' programming languages.

" The CISCs that failed - DEC VAX and the Motorola 68000 - were the most CISCy.

Most instructions were variable length.

Some frequently used instructions could be very long.

Many instructions had microcode.

Many operations had side effects.

They had complicated addressing modes - elegant in their generality, but complicated, sometimes necessitating microcode just to calculate an address. " -- https://www.semipublic.comp-arch.net/wiki/RISC_versus_CISCLinks:

A descendent is the ColdFire? processor, which is a simplified 68000

todo

floating point unit also has:

MAC (multiply accumulate) unit also has:

Addressing modes:

todo

Links:

highly recommended:

todo explain

" Registers

The 6502's registers include one 8-bit accumulator register (A), two 8-bit index registers (X and Y), an 8-bit processor status register (P), an 8-bit stack pointer (S), and a 16-bit program counter (PC). The stack's address space is hardwired to memory page $01, i.e. the address range $0100–$01FF (256–511). Software access to the stack is done via four implied addressing mode instructions, whose functions are to push or pop (pull) the accumulator or the processor status register. The same stack is also used for subroutine calls via the JSR (Jump to Subroutine) and RTS (Return from Subroutine) instructions and for interrupt handling. "

better description of registers at: http://skilldrick.github.io/easy6502/

http://www.obelisk.demon.co.uk/6502/registers.html

" Addressing

The chip uses the index and stack registers effectively with several addressing modes, including a fast "direct page" or "zero page" mode, similar to that found on the PDP-8, that accesses memory locations from addresses 0 to 255 with a single 8-bit address (saving the cycle normally required to fetch the high-order byte of the address)—code for the 6502 uses the zero page much as code for other processors would use registers. On some 6502-based microcomputers with an operating system, the OS uses most of zero page, leaving only a handful of locations for the user.

Addressing modes also include implied (1 byte instructions); absolute (3 bytes); indexed absolute (3 bytes); indexed zero-page (2 bytes); relative (2 bytes); accumulator (1); indirect,x and indirect,y (2); and immediate (2). Absolute mode is a general-purpose mode. Branch instructions use a signed 8-bit offset relative to the instruction after the branch; the numerical range -128..127 therefore translates to 128 bytes backward and 127 bytes forward from the instruction following the branch (which is 126 bytes backward and 129 bytes forward from the start of the branch instruction). Accumulator mode uses the accumulator as an effective address, and does not need any operand data. Immediate mode uses an 8-bit literal operand. Indirect addressing

The indirect modes are useful for array processing and other looping. With the 5/6 cycle "(indirect),y" mode, the 8-bit Y register is added to a 16-bit base address read from zero page which is located by a single byte following the opcode. The Y register is therefore an index-register in the sense that it is used to hold an actual index (as opposed to the X register in the 6800 where a base address was directly stored and to which an immediate offset could be added). Incrementing the index register to walk the array byte-wise takes only two additional cycles. With the less frequently used "(indirect,x)" mode the effective address for the operation is found at the zero page address formed by adding the second byte of the instruction to the contents of the X register. Using the indexed modes, the zero page effectively acts as a set of up to 128 additional (though very slow) address registers. "

better description of addressing modes at: http://skilldrick.github.io/easy6502/

" The 6502 is technically not a RISC design, however, as arithmetic operations can read any memory cell (not only zero-page), and some instructions (INC, ROL, etc.) even modify memory (i.e. they are read-modify-write instructions), contrary to the basic load/store philosophy of RISC. Furthermore, orthogonality is equally often associated with "CISC".

instructions: http://www.obelisk.demon.co.uk/6502/instructions.html

http://www.visual6502.org/JSSim/index.html

toread for fun: http://archive.archaeology.org/1107/features/mos_technology_6502_computer_chip_cpu.html

toread for fun: http://www.righto.com/2013/01/a-small-part-of-6502-chip-explained.html

toread for fun: http://research.swtch.com/6502

" Used in such greats as the Apple II, all the Acorn machines, the Orics and more. Somewhat simpler device than the Z80 with fewer instructions, fewer addressing modes and fewer registers. Just the minimum compliment of Accumulator, X and Y in fact. It did have the unique ability though to access the first page of memory (0000h to 00ffh) much faster than the rest of memory.

Many people claim now that the 6502 was the first 'RISC' chip, although there weren't many instructions to 'reduce'. If you stretch the point that zero page fast access was akin to having lots of registers though, that sounds slightly RISC-like. It was completely un-RISC-like in that zero page was only good for storing data (and incrememting, decrememting IIRC), all arithmetic had to be done on the Accumulator, and although X and Y were both 'indexing' registers, there were some sorts of indexing that only X could do, and others that only Y could do. " -- http://www.landley.net/history/mirror/acorn/processors.html

todo

according to Wikipedia ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/8051#Important_features_and_applications ), two distinctive and important features of the 8051 are bit-level boolean logic operations, which "helped cement the 8051's popularity in industrial control applications because it reduced code size by as much as 30%.", and "four bank selectable working register sets which greatly reduce the amount of time required to complete an interrupt service routine. With a single instruction the 8051 can switch register banks as opposed to the time consuming task of transferring the critical registers to the stack or designated RAM locations. These registers also allowed the 8051 to quickly perform a context switch."

links:

RISC is "Reduced Instruction Set Computer", in contrast to CISC, "Complex Instruction Set Computer". The difference between RISC and CISC is not that RISC necessarily has fewer instructions (although it often does), but rather that RISC instructions are less complex and typically can be executed within a single data memory cycle ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reduced_instruction_set_computing#Instruction_set ). Note that this means that RISC instruction sets sometimes eschew operations which access main memory and also do something else, preferring to provide only load/store operations and not other ways of accessing main memory.

The term is not very well defined: "the statement in the 70s about (801/)RISC was that it could be done in a single chip. later in the 80s, (801/)RISC was instructions that could be executed in single machine cycle. Over the decades, the definition of RISC has been somewhat fluid ... especially as the number of circuits in a chip has dramatically increased." -- Lynn Wheeler, https://www.semipublic.comp-arch.net/wiki/RISC_versus_CISC

Here's an attempt to define it:

" what exactly is a RISC processor? This turns out to be quite hard to answer. Here is a list of possible criteria that have been used in the past.

Instructions are conceptually simple — that is, no baroque things like `evaluate polynomial', or `edit string', both of which were found in the VAX.

Instructions are uniform length — as opposed, to say, the VAX or M68000 which have a wide range of instruction lengths.

Instructions use one, or very few, formats — again, unlike the VAX or M68000.

The instruction set is orthogonal — that is, there are no special rules about what operations are permitted with particular addressing modes (which would complicate the life of a compiler writer).

There is one, or very few, addressing modes.

The architecture is load-and-store — that is, only load and store operations access memory — all operate instructions (e.g. arithmetic) only operate on registers.

The architecture supports two (or perhaps a few more) datatypes — integer and floating point usually." -- http://euler.mat.uson.mx/~havillam/ca/CS323/0708.cs-323004.html(note:

orthogonality: in processor ISAs, 'orthogonal' seems to refer to:

)

As of this writing, ARM is the most commerical successful RISC architecture. Other often-noted ones are SPARC, PowerPC?, and MIPS. Of these, some say that MIPS is the prototypical, most elegant example of RISC:

"MIPS is the cleanest successful RISC. PowerPC? and (32-bit) ARM have so many extra instructions (even a few operating modes, 32-bit ARM especially) that you could almost call them CISC. SPARC has a few odd features and Itanium is composed entirely of odd features. The latter two are more dead than MIPS." -- http://stackoverflow.com/a/2653951/171761

"Answering now your first question: the reason that MIPS features so prominently in books is that it is almost a perfect exemplar of a RISC system. It is a small, relatively pure RISC implementation that is easily understood and that illustrates RISC concepts well. For pedagogical purposes it is probably the best real-world architecture to show the nature of RISC, along with its warts. Other processors thought of as RISC (ARM, SPARC, Alpha, etc.) are more pragmatic and complicated, obfuscating RISC concepts with some more CISC-like enhancements for better performance or other benefits." -- http://stackoverflow.com/a/2796869/171761

"Almost every instruction found in the MIPS core is found in the other architectures" -- http://www.cis.upenn.edu/~milom/cis501-Fall05/papers/RISC-appendix-C.pdf

"MIPS is the most elegant among the effective RISC architectures; even the competition thought so, as evidenced by the strong MIPS influence to be seen in later architectures like DEC’s Alpha and HP’s Precision. Elegance by itself doesn’t get you far in a competitive marketplace, but MIPS microproces- sors have generally managed to be among the most efficient of each generation by remaining among the simplest" --- http://v5.books.elsevier.com/bookscat/samples/9780120884216/9780120884216.PDF

In addition, there are 8-bit microcontrollers ("MCUs"), which are not considered in the same class as CPUs but which also have interesting, small intruction sets. The PIC and the AVR architectures are popular ones (the 8051 is also popular but is older, is CISC, and does not seem to be recommended as often; however PIC and AVR are only manufactored by their respective developers, whereas 8051-compatibles are manufactored by a bunch of different companies). Note that Arduino, which you may have heard of, uses AVR or ARM. Many people comment that the AVR is easier to program than the (8-bit) PIC ( http://stackoverflow.com/questions/140049/avr-or-pic-to-start-programming-microcontroller , http://www.ladyada.net/library/picvsavr.html ), but others say that PIC is simpler (e.g. http://www.8051projects.net/lofiversion/t17539/what039s-diff039-between-8051pic-avr.html ); i suspect that they mean that the PIC has fewer instructions and a simpler architecture outside of the ISA, but the AVR has a more uniform architecture and more accessible C compilers, but i'm not too sure what they mean since i've never used either. The PIC and the AVR are both called RISC by some but the AVR has a more RISC-y design (the PIC has indirect addressing), even though it also has a larger instruction set.

" Goals of the 64bit MIPS architecture:

Use general-purpose registers with a load-store architecture

Support these addressing modes: displacement (with an address offset size of 12–16 bits), immediate (size 8–16 bits), and register indirect

Support these data sizes and types: 8-, 16-, 32-, and 64-bit integers and 64-bit IEEE 754 floating-point numbers

Support these simple instructions, since they will dominate the number of instructions executed: load, store, add, subtract, move register-register, and shift

Compare equal, compare not equal, compare less, branch (with a PC-relative address at least 8 bits long), jump, call, and return

Use fixed instruction encoding if interested in performance, and use variable instruction encoding if interested in code size

Provide at least 16 general-purpose registers, be sure all addressing modes apply to all data transfer instructions

Aim for a minimalist instruction setMIPS addressing modes

The data types are 8-bit bytes, 16-bit half words, 32-bit words, and 64-bit double words for integer data and 32-bit single precision and 64-bit double precision for floating point

The only data addressing modes are immediate and displacement, both with 16-bit fields

Register indirect is accomplished simply by placing 0 in the 16-bit displacement field

Absolute addressing with a 16-bit field is accomplished by using register 0 as the base register

MIPS memory is byte addressable with a 64-bit address

Mode bit that allows software to select either Big Endian or Little Endian" Goals of the 64bit MIPS architecture:

Use general-purpose registers with a load-store architecture

Support these addressing modes: displacement (with an address offset size of 12–16 bits), immediate (size 8–16 bits), and register indirect

Support these data sizes and types: 8-, 16-, 32-, and 64-bit integers and 64-bit IEEE 754 floating-point numbers

Support these simple instructions, since they will dominate the number of instructions executed: load, store, add, subtract, move register-register, and shift

Compare equal, compare not equal, compare less, branch (with a PC-relative address at least 8 bits long), jump, call, and return

Use fixed instruction encoding if interested in performance, and use variable instruction encoding if interested in code size

Provide at least 16 general-purpose registers, be sure all addressing modes apply to all data transfer instructions

Aim for a minimalist instruction setRegisters in MIPS

32 64-bit general-purpose registers (GPRs), sometimes called integer registers, named R0, R1, ... , R31.

32 floating-point registers (FPRs), named F0, F1, ... , F31, which can hold 32 single-precision (32-bit) values or 32 double-precision (64-bit) values

When holding one single-precision number, the other half an FPR is unused

R0 is always 0MIPS addressing modes

The data types are 8-bit bytes, 16-bit half words, 32-bit words, and 64-bit double words for integer data and 32-bit single precision and 64-bit double precision for floating point

The only data addressing modes are immediate and displacement, both with 16-bit fields

Register indirect is accomplished simply by placing 0 in the 16-bit displacement field

Absolute addressing with a 16-bit field is accomplished by using register 0 as the base register

MIPS memory is byte addressable with a 64-bit address

Mode bit that allows software to select either Big Endian or Little EndianMIPS instruction format

2 addressing modes that are to be encoded in the opcode

32 bit instructions (6 bit primary opcode)MIPS operations

4 classes of operations (loads and stores, ALU operations, branches and jumps, and floating-point operations)

Any of the general-purpose or floating-point registers may be loaded or stored

Loading R0 has no effect

Single-precision floating-point numbers occupy half a floating-point register

Conversions between single and double precision must be done explicitly

All ALU instructions are register-register instructions (add, subtract, AND, OR, XOR, and shifts) with immediate forms provided using a 16-bit sign-extended immediate

Flow Control:

Compare instructions: compare two registers to see if the first is less than the second. If true, a 1 is placed in the destination register (to represent true); otherwise a 0 is placed. Also called "set" operations because they set a register

Jump instructions are differentiated by the two ways to specify the destination address and by whether or not a link is made

Two types of jumps: plain jump and jump and link which places the return address in

All branches are conditional specified by instruction which may test the register source for zero or nonzero, whether it contains a data value or the result of a compare, whether it's negative or equal to another register

Floating point:

Instructions indicate whether there is single or double precision (.S or .D)

MIPS64 can perform two 32-bit operations on a single 64-bit register with paired single operations (.PS)"

in MIPS they have beq and bne but they replace ble etc with stuff like 'set if less than (a, b, r0); beq (r0, zero, LABEL)': http://www.cs.umd.edu/class/sum2003/cmsc311/Notes/Mips/pseudojump.html

with variants for addressing mode and type and special registers omitted:

add and beq bne div j jal (jump and link) load mult nor xor or store slt (set to 1 if less than) sll (lsl) srl (lsr) sra (asr) sub

DLX is MIPS for education

with variants for addressing mode and type and special registers omitted:

load, store lhi (load high immediate) mov add sub mult div and or sll (lsl) srl (lsr) sra (asr) slt (set if less than) sgt, sle, sge, sne beqz, bneq bfpg, bfpf (branch on comparison bit in the FP status register) j jal (jump and link) trap rfe (return to user code from exception) cvt (convert) LTF, GTF, LEF, GEF, EQF, NEF (compare and set comparison bit in the FP status register)

Links:

"The AVR processors were designed with the efficient execution of compiled C code in mind and have several built-in pointers for the task.... The mostly regular instruction set makes programming it using C (or even Ada) compilers fairly straightforward. GCC has included AVR support for quite some time, and that support is widely used. In fact, Atmel solicited input from major developers of compilers for small microcontrollers, to determine the instruction set features that were most useful in a compiler for high-level languages." -- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atmel_AVR#Device_overview

Most AVRs are modified Harvard architecture designs. Harvard architecture means that program code and data are stored in separate memory banks. Modified Harvard architecture means that program code can still be accessed. Most, but not all AVRs can access program code in a read-only fashion; some AVRs can also write to program code memory. The smallest AVRs have 512 bytes of program memory and 32 bytes of data memory.

Here we look at the AVR Minimal Core ISA, found in: ATtiny11, ATtiny12, ATtiny15, ATtiny28. Note that i think the "Reduced Core" may be more current, found in: ATtiny10, ATtiny9, ATtiny5, ATtiny4. I'll omit explanations for instruction that can be guessed from the mnemonic when the mnemonic follows the same pattern as previously listed instructions.

The AVRs have 16 or more general purpose registers. The registers are mapped to RAM. This is a load-store architecture; only the load and store operations access RAM, everything else works with registers. The AVR has a status register composed of 8 flags: Carry, Zero, Negative, Overflow (V), Sign, Half carry (for Binary Coded Decimal arithmetic), Bit copy, Interrupts enabled. Most recent AVRs have an on-chip oscillator. Most AVRs have a 2-stage pipelined architecture ("the next instruction is fetched as the current one is executing") and most instructions are single cycle, allowing almost 1 MIPS per MHZ (e.g. an 8 MHz processor can achieve 8 MIPS). AVRs have a 'watchdog timer', which can be used to generate an interrupt or to reboot (reset) the MCU after some amount of time; if enabled, the watchdog timer is continually counting up and the software must periodically reset it with the WDR instruction to prevent it from activating (e.g. it can be used as a timeout failsafe so you don't have to manually reboot hung devices in the field). Most AVRs support JTAG, a debugging and program-code loading mechanism. The stack is allocated out of ordinary RAM and can grow to the entire RAM size. Four addressing modes are supported (at least in Reduced Core): direct, indirect, indirect with pre-decrement, and indirect with post-increment.

Arithmetic instructions: ADD, ADC (add with carry), SUB (subtract), SUBI (subtract immediate), SBC (subtract with carry), SBCI, NEG, INC (increment), DEC, TST (test for zero or minus), CLR (clear register), SER (set register). The AVR Minimal Core ISA does not contain a MUL (multiplication) instruction but the AVR Enhanced Core ISA does.

Branches: RJMP (relative jump), RCALL (relative subroutine call), RET (subroutine return), RETI (interrupt return), CPSE (compare, skip if equal), CP (compare), CPC (compare with carry), CPI (compare immediate), SBRC (skip if bit in register cleared), SBRS, SBIC (skip if bit in I/O register cleared), SBIS, BRBS (branch if status flag set), BRBC (branch if status flag cleared), BREQ (branch if equal), BRNE (branch if not equal), BRCS (branch if carry set), BRCC, BRSH (branch if same or higher), BRLO (branch if lower), BRMI (branch if minus), BRPL (branch if plus), BRGE (branch if greater-than-or-equal, signed), BRLT, BRHS (branch if half-carry set), BRHC, BRTS (branch if T set), BRTC, BRVS (branch if overflow set), BRVC

Transfers: LD (load from memory), ST (store to memory), MOV (move), LDI (load immediate), IN (load from I/O memory), OUT, LPM (load from program memory). The AVR Reduced Core uses LD for program and data memory. The AVR Reduced Core has PUSH and POP instructions. The AVR Minimal Core ISA does not contain a SPM (store to program memory) instruction but the AVR Enhanced Core ISA does.

Bitwise: SBI (set bit in I/O register), CBI, LSL (logical shift left), LSR (logical shift right), ROL (rotate left thru carry), ROR, ASR (arithmetic shift right), SWAP (swap nibbles), BSET (flag set), BCLR, BST, BLD (bit load from T to register), SEC (set carry), CLC (clear carry), SEN, CLN, SEZ, CLZ, SES, CLS, SEV, CLV, SET, CLT, SEH, CLH, AND, ANDI (AND immediate), OR, ORI, EOR (xor), COM (bitwise negation (one's complement)), SBR (set register bit), CBR (clear register bit),

Control: SEI (set interrupt), CLI, BRIE (branch if interrupt enabled), BRID (branch if interrupt disabled), NOP, SLEEP (sleep until interrupt), WDR (reset watchdog timer)

Summary description: We have: load/store, mov, relative jump, relative call/return, <=/</=/>,>= comparison and branching, arithmetic (addition, subtraction, negation, comparisons and set/clears for carry/negative/overflow/zero flags and various registers; many arithmetic operations have multiple forms for carry/no-carry) bitwise arithmetic (negation, and, or, xor, set/clear/skip-if bit, logical shifts, arithmetic shifts, rotate, swap nibbles), and interrupts, NOP, sleep (until interrupt) and watchdog timer reset.

"

" > The main problem I had with the AVR's (for "bigger" applications in > C), is the contortions you have to go through to access constant data > in flash. It has a "harvard" architecture, meaning you need a > different pointer type to access data stored in the "program" > space. This makes it hard to write general purpose functions which are > equally happy working on RAM and flash data. While in principle I > think the compilers could hide this, as far as I know they all have > similar clumsy work-arounds which end up infecting many of your > function and variable definitions. (This is for the case when you have > quite a lot of constant data, too much to make a ram copy. For example > CRC tables, menu structures & screen layouts, fonts.) >

Yes, that's definitely a problem, and one of the weak points of the AVR core (the other main weaknesses are poor pointer register support, and no SP+offset addressing). " -- http://www.embeddedrelated.com/usenet/embedded/show/102808-1.php

Links:

The PIC design is a Harvard architecture. It has:

"

There is no distinction between memory space and register space because the RAM serves the job of both memory and registers, and the RAM is usually just referred to as the register file or simply as the registers....The addressability of memory varies depending on device series, and all PIC devices have some banking mechanism to extend addressing to additional memory...To implement indirect addressing, a "file select register" (FSR) and "indirect register" (INDF) are used. A register number is written to the FSR, after which reads from or writes to INDF will actually be to or from the register pointed to by FSR....PICs have a hardware call stack, which is used to save return addresses....Some operations, such as bit setting and testing, can be performed on any numbered register, but bi-operand arithmetic operations always involve W (the accumulator), writing the result back to either W or the other operand register. To load a constant, it is necessary to load it into W before it can be moved into another register. On the older cores, all register moves needed to pass through W, but this changed on the "high end" cores....PIC cores have skip instructions which are used for conditional execution and branching. The skip instructions are 'skip if bit set' and 'skip if bit not set'. Because cores before PIC18 had only unconditional branch instructions, conditional jumps are implemented by a conditional skip (with the opposite condition) followed by an unconditional branch.

In general, PIC instructions fall into 5 classes:

... The architectural decisions are directed at the maximization of speed-to-cost ratio. The PIC architecture was among the first scalar CPU designs,[citation needed] and is still among the simplest and cheapest. The Harvard architecture—in which instructions and data come from separate sources—simplifies timing and microcircuit design greatly, and this benefits clock speed, price, and power consumption.

The PIC instruction set is suited to implementation of fast lookup tables in the program space. Such lookups take one instruction and two instruction cycles. Many functions can be modeled in this way. Optimization is facilitated by the relatively large program space of the PIC (e.g. 4096 × 14-bit words on the 16F690) and by the design of the instruction set, which allows for embedded constants. For example, a branch instruction's target may be indexed by W, and execute a "RETLW" which does as it is named - return with literal in W. ...

Limitations

One accumulator

Register-bank switching is required to access the entire RAM of many devices

Operations and registers are not orthogonal; some instructions can address RAM and/or immediate constants, while others can only use the accumulatorThe following stack limitations have been addressed in the PIC18 series, but still apply to earlier cores:

The hardware call stack is not addressable, so preemptive task switching cannot be implemented

Software-implemented stacks are not efficient, so it is difficult to generate reentrant code and support local variablesWith paged program memory, there are two page sizes to worry about

...

The easy to learn RISC instruction set of the PIC assembly language code can make the overall flow difficult to comprehend. Judicious use of simple macros can increase the readability of PIC assembly language.

...

Baseline core devices (12 bit)

These devices feature a 12-bit wide code memory, a 32-byte register file, and a tiny two level deep call stack. They are represented by the PIC10 series, as well as by some PIC12 and PIC16 devices.

...

Generally the first 7 to 9 bytes of the register file are special-purpose registers, and the remaining bytes are general purpose RAM. Pointers are implemented using a register pair: after writing an address to the FSR (file select register), the INDF (indirect f) register becomes an alias for the addressed register. If banked RAM is implemented, the bank number is selected by the high 3 bits of the FSR. This affects register numbers 16–31; registers 0–15 are global and not affected by the bank select bits.

Because of the very limited register space (5 bits), 4 rarely read registers were not assigned addresses, but written by special instructions (OPTION and TRIS).

The ROM address space is 512 words (12 bits each), which may be extended to 2048 words by banking. CALL and GOTO instructions specify the low 9 bits of the new code location; additional high-order bits are taken from the status register. Note that a CALL instruction only includes 8 bits of address, and may only specify addresses in the first half of each 512-word page.

Lookup tables are implemented using a computed GOTO (assignment to PCL register) into a table of RETLW instructions. ...

" -- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PIC_microcontroller

Instructions (remember that W is the accumulator; f is a register number):

misc: NOP, OPTION (copy W to option register), SLEEP, CLRWDT (reset watchdog timer), TRIS k (k = 1,2, or 3) (copy W to one of the tristate registers; tristate registers control port I/O direction; "in 12bit cores, the TRISn registers are not mapped in the file registers space, so the TRIS instruction is the only way of setting port direction for those processors." -- http://www.microchip.com/forums/m157552.aspx ),

moves: MOVF f r (r = f), MOVWF r (f = W)

set/clears:

bitwise arithmetic:

arithmetic:

skips:

control flow:

immediate addressing mode operations (e.g. operations that take a constant parameter):

Summary: PIC's ISA is a non-regular design in that the accumulator register has a special role (every binary operation takes the accumulator as one operand; many operations cannot take constant operands; and constants can only be directly placed into W (and then can be moved into another register with a MOVWF instruction). There are moves, clears, bit sets and clears, bitwise arithmetic (and, or, xor, not, swap nibbles, rotate-right/left-thru-carry; only and, or, xor can have a constant operand), arithmetic (add, subtract, increment, decrement), skips (inc/dec and skip if zero; skip if bit is set/clear), control flow (call/return, goto). As noted above, there is an idiomatic lookup-table-in-program-memory implementation using RETLW k instructions to encode each table entry.

Links:

todo

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ARM_architecture#32-bit_architecture

http://users.ece.utexas.edu/~valvano/EE345M/Arm_EE382N_4.pdf

https://sourceware.org/cgen/gen-doc/arm-thumb-insn.html list of instructions with names, todo

A recent addition to the ARM ISA family is ARM64 (ARMv8 A64 / AArch64), described on the pages http://www.arm.com/products/processors/instruction-set-architectures/index.php http://infocenter.arm.com/help/index.jsp?topic=/com.arm.doc.dui0677b/ch01s01.html http://www.arm.com/files/downloads/ARMv8_Architecture.pdf http://www.cs.utexas.edu/~peterson/arm/DDI0487A_a_armv8_arm_errata.pdf http://www.arm.com/files/pdf/ARMv8R__Architecture_Oct13.pdf.

ARM has various versions and 3 profiles; A (full-features for use as e.g. CPU of smartphone or computer; has virtual addressing MMU), R (real-time, for use in e.g. car engines; has deterministic (i think) physical addressing MMU), M (microcontroller; only supports Thumb ISA). The latest version is v8, but according to the ARM Wikipedia page only A and R profiles are (yet) available for v8. v7 has all 3 profiles (e.g. http://web.eecs.umich.edu/~prabal/teaching/eecs373-f10/readings/ARMv7-M_ARM.pdf ). There's also an E-M which is like M with a DSP extension, found in v7.

ARM Thumb: "The Thumb instruction set is a subset of the most commonly used 32-bit ARM instructions." -- (ARM7TDMI Technical Reference Manual Revision: r4p1) "The Thumb instruction set provides better code density, at the expense of inferior performance....Thumb-2, a major enhancement of the Thumb instruction set. Thumb-2 provides almost exactly the same functionality as the ARM instruction set. It has both 16-bit and 32-bit instructions, and achieves ARM-like performance with Thumb-like code density." -- (RealView? Compilation Tools Assembler Guide Version 4.0) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ARM_Cortex-M

"The biggest register difference involves the SP register. The Thumb state has unique stack mnemonics (PUSH, POP) that don't exist in the ARM state. These instructions assume the existence of a stack pointer, for which R13 is used. They translate into load and store instructions in the ARM state. " -- http://www.embedded.com/electronics-blogs/beginner-s-corner/4024632/Introduction-to-ARM-thumb

"The original Thumb-Instruction set only contained 16-bit instructions. Thumb2 introduced mixed 16/32 bit instructions....The ARM processor has 2 instruction sets, the traditional ARM set, where the instructions are all 32-bit long, and the more condensed Thumb(2) set, where most common instructions are 16-bit long (and some are 32-bit long)." -- http://stackoverflow.com/questions/10638130/thumb-instruction-in-arm

Some instructions have immediate addressing modes and others do not. i won't bother to include that information because my interest here is mainly in the instruction set. I leave out some instructions that are, to me, uninteresting variants of existing ones. Note that the purpose of these listings is not accuracy, but rather to get a sense of what sorts of instructions are in RISC-ish CPU instruction sets.

Note that in Thumb2, instructions cannot reference the PC (program counter) or SP (stack pointer) as operands, including destination operand, unless noted. Note that every instruction that returns a result takes an operand specifying the destination register; operations are NOT done in place on the input registers (except when the destination register given is the same as an input register).

ARM has 'barrel shifting', meaning that shifts and rotates can be performed on operands without issuing separate instructions.

It has a clever way of representing 32-bit immediate values with only 8 bits plus 4 bits to determine a shift, which allows it to represent any power of 2 as an immediate value: http://alisdair.mcdiarmid.org/2014/01/12/arm-immediate-value-encoding.html . "Thumb-2 immediate encoding is even more gleeful--in addition to allowing rotation, it also allows for spaced repetition of any 8-bit pattern (common in low level hack patterns, like from [1]) to be encoded in single instructions." -- https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=7046803 . If the value you want isn't accessible as an immediate, you can load it from a constant table or you can compute it, or some instruction sets have MOVW and MOVT which can construct and combine 16-bit immediates into a 32-bit value. Some assemblers let you just specify the immediate and the assembler figures out how to get it ( https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=7045898 ).

ARM instructions traditionally encoded a conditional execution field, allowing instructions to be skipped depending on the flags, without doing a branch. On ARM64 this has been changed:

" arm64 ... sort of ditches conditional execution. It’s not on every instruction any more, but it’s still available on more instructions than on most other arches.

To the usual complement of typical conditional instructions (branch, add/sub with carry, select and set), arm64 adds select with increment, negate, or inversion, the ability to conditionally set to -1 as well as +1, and the ability to conditionally compare and merge the flags in a fairly flexible manner (it’s really a conditional select of condition flags between the result of a comparison and an immediate). This actually preserves most of the power of conditional execution (except for really exotic hand-coded usages), while taking up much less encoding space. " -- stephencanon , https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=7047762

ARM has 8 Operating Modes ). "Each mode has its own mode-specific registers, including a status register":

(descriptions from http://www.cs.virginia.edu/~skadron/cs433_s09_processors/arm11.pdf )

Addressing modes ( http://www.cs.uregina.ca/Links/class-info/301/ARM-addressing/lecture.html ):

MOV LSL r1 r2 r3 (logical shift left; r1 := r2 << r3) LSR ASR (arithmetic shift left) ADD (note; the source and/or destination operands for ADD can include SP, the stack pointer; in this way you can get the SP into a register) SUB (note; the source and destination operands for SUB can include SP, the stack pointer)

ADR (Add immediate to program counter; in this way you can get the PC into a register; useful for getting the address of a 'label' if your assembler translates labels to relative offsets )

CMP

AND EOR (xor)

ADC (Add with Carry; a + b + carry bit) SBC (Subtract with Carry; a - b - carry bit) ROR (Rotate Right) TST (Test bits: TST x y: update condition code flags on Rn AND Rm) RSB (Reverse subtract (from zero; e.g. negate)) CMP (update condition code flags on Rn - Rm) CMN (Compare Negative; update condition code flags on Rn + Rm) ORR (or) MUL BIC (Bit Clear: x AND (NOT y)) MVN (Move Negative/NOT: binary negation)

BL (branch with link; BL <label>: LR register = address of next instruction, PC = label)

BX (Branch and Exchange; this is used to enter/exit "thumb state") BLX (Branch with Link and Exchange; this is used to enter/exit "thumb state")

Load and store:

STR (Store word. Addressing modes include immediate, register offset, PC offset, SP offset. Can store list of multiple registers (STMIA).) also STRH for store halfword, STRB for byte

LDR (Load word. Addressing modes include immediate, register offset, SP offset. Can load list of multiple registers (LDMIA).) also LDRH for Load unsigned halfword, LDRSH for signed halfword, LDRB for unsigned byte, LDRSB for signed byte

LDR (load from literal pool instrs) B (unconditional, conditional branch instructions: takes as an operand a 'condition field' (this is different from a condition code), which is one of equal, not equal, Carry Set / Unsigned higher or same, Carry Clear / Unsigned lower, Negative, Positive or zero, Overflow, No overflow, Unsigned higher, Unsigned lower or same, Signed greater than or equal, Signed less than or equal, Signed greater than, Signed less than, always

SVC (service (system) call instructions; formerly SWI) SETEND (set endianness) CPS (change processor state; enables and disables specified interrupts) BKPT (software breakpoint) IT (If-Then; "Makes up to four following instructions conditional, according to pattern. pattern is a string of up to three letters. Each letter can be T (Then) or E (Else)."

Adjust stack pointer instructions Increment stack pointer ADD (SP plus immediate) Decrement stack pointer SUB (SP minus immediate)